Driven by beliefs shaped in our childhood and largely subconscious, our attitudes to money and our associated behaviours are possibly the single biggest determinant of our financial – and mental – wellbeing.

Negative money attitudes, when combined with our tendencies to succumb to cognitive biases when decision making, can sabotage our happiness, by placing enormous obstacles in the way of us achieving our career, relationship, and lifestyle goals.

Financial advisers are ideally placed to help their clients achieve more positive relationships with money, not by helping them acquire more of it (although that is usually an outcome), but by fundamentally reshaping their money attitudes and behaviours, and giving them a framework within which they can make better financial decisions. Further emotional benefits also accrue to advice clients from the advice proves itself, which reinforces a sense of achievement and progress towards goals.

This reimagined role for advisers in coaching better money behaviours – which is already starting to play out in the market in response to consumer demand – has significant implications for adviser training and advice processes. More importantly, and more excitingly, this new perspective on how advisers create value for their clients implies:

The relationship between our finances and our stress levels is both intuitive and borne out across an extensive body of research.

According to one survey of Australian adults1 , around one quarter reported moderate to extremely severe depressive symptoms. And across the community, personal financial issues are the biggest driver of stress, cited by 49% of respondents.

Financial issues can kill our relationships too. According to Relationships Australia, 7 out of 10 couples report that money causes tension in their relationships, and disagreement over finances is a stronger predictor of divorce than other commonly cited causes of marital disagreements2 .

Disturbingly, these results probably still understate the extent to which are most common money emotions are negative.

When psychologist Adrian Furnham3 , studied the emotions people had associated with money over the prior 12 months, the top 4 in ranked order were Anxiety, Depression, Anger and Helplessness. Indeed, 8 of the top 10 ranked emotions were all negative, as shown in Table 1.

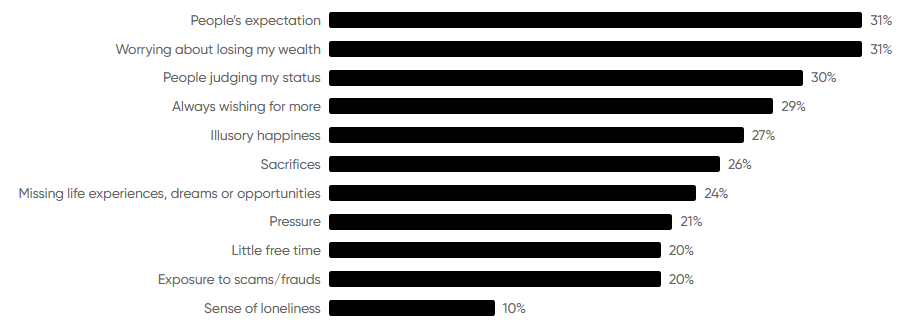

And, as a US survey found , even amongst those who have accumulated substantial wealth, negative sentiments remain common:

And, as a US survey found4 , even amongst those who have accumulated substantial wealth, negative sentiments remain common:

According to experts, our relationship with money is driven by a complex array of beliefs, attitudes, and behaviours, many of which were shaped early in our lives by the interplay between familial, ethnic, and cultural influences, and then further refined by our exposure to media messages. So powerful can these beliefs and attitudes be, they can effectively negate any financial knowledge we have acquired and contribute to us making sub-optimal financial decisions5.

Financial psychologists Bradley Klontz and Ted Klontz refer to the term “money script” to describe these core beliefs about money6 . These beliefs are typically unconscious and likely learned during childhood and adolescence, influenced by our parents’ own money attitudes and behaviours. For example, were they frugal? Were they judgemental about others based on how much money those people had?

If our parents had a healthy relationship with money, (irrespective of their wealth) and talked openly about financial matters, then our attitudes and behaviours are likely to be similar. Conversely, if money was associated with some measure of shame or trauma – money wounds as author Ken Honda7 refers to them – then we are highly likely to enter adulthood with an unhealthy relationship with money, increasing the likelihood we will make poor financial decisions.

References

01 Stress and Wellbeing, how Australians are Coping with Life, Stress and Wellbeing Survey 2015, Australian Psychological Society.

02 Relationships Australia Online Survey, August 2015, relationships.org.au

03 The New Psychology of Money, A. Furnham, Routledge, May 2014.

04 The Why of Wealth Survey 2018, Boston Private, bostonprivate.com

05 Financial Wellbeing, a conceptual model and preliminary analysis, E. Kempson, A. Finney & C. Poppe, Consumption Research Norway – SIFO, 2017.

06 Money beliefs and financial behaviours: development of the Klontz money script inventory, Journal of Financial Therapy, Volume 2, Issue 1, 2011.

07 Happy Money: the Japanese art of making peace with your money, K. Honda, Gallery Books, 2019.

Money Beliefs and Behaviours

Compounding our money beliefs are our decision-making flaws

In contrast to classical models of economics which assume consumers to be rational financial decision makers, behavioural economics uses insights from psychology and sociology to create a much more realistic picture of the factors affecting our behaviour in financial matters.

Behavioural economists draw on the long list of “heuristics” – mental shortcuts or biases in the way we think – developed by cognitive psychologists. The interaction between many of these has been shown to undermine our financial decision making, especially in relation to events which are in the future.

Loss Aversion: We weigh losses twice as much as gains of the same value

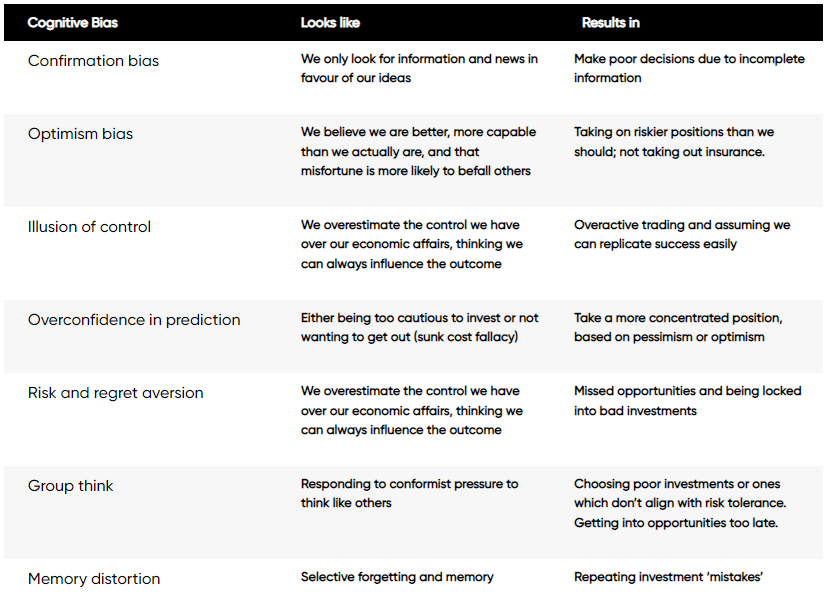

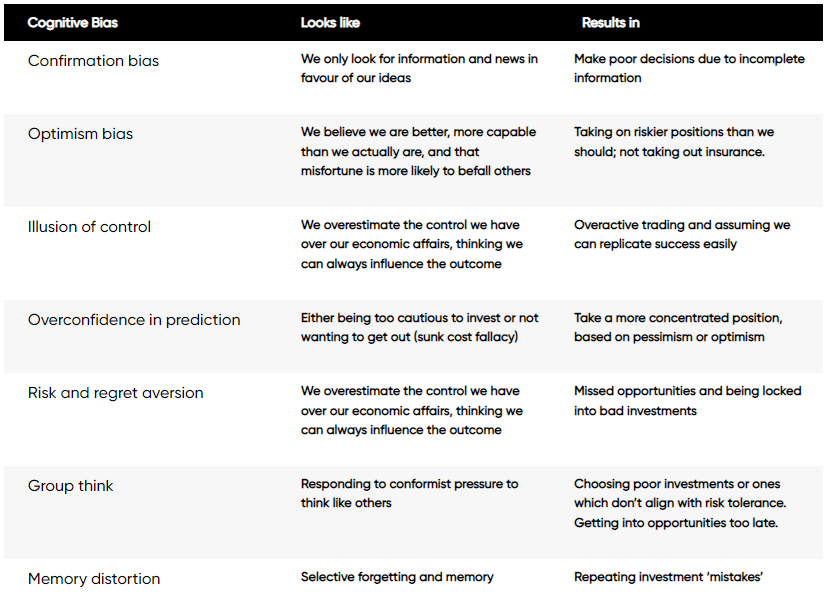

ASIC Report 2308 listed more than 30 of these biases that were thought particularly relevant to financial decision making, although for our purposes, the work of Furnham9 in distilling them down to the ‘7 Deadly Sins of Investing’ is a more practical demonstration:

Table 2 The Seven Deadly Sins of Investing

Source: Furnham

Money archetypes

The various combinations of these different money scripts, behaviours and decision making – overlaid with our current economic and social circumstances – manifest as money types.

While there are various money type methodologies, the ‘8 type’ model – developed by the Money Coaching Institute 20 – is preferred by many local advisers. The types are explained in more detail below.

Delivering any kind of financial advice effectively requires an understanding of which type – or types – a person exhibits at a point in time (they may exhibit different types at different points in their lives and can be coached out of, and into, different types).

The Innocent

As children we start of as Innocents. The ‘Innocent’ archetype is one of the most common money types in women. This type feels overwhelmed, and reacts by burying their head in the sand, avoiding bills, superannuation statements, bank and credit card statements, indeed anything relating to money. They feel powerless and anxious, and will be

Immobilized around money matters without the opinions and guidance of others.

The Victim

The victim blames their money challenges on some event or combination of factors from earlier in their life (money wounds). The recognition that they need help is countered by the shame of believing they can’t help themselves.

They may feel entitled to a rescue of some form – because of all the wounds they have had to bear.

Addictions, such as gambling, shopping, or substance abuse, are common signs of this Money type and can sabotage their sense of financial well-being and security.

The Warrior

The Warrior sets out to conquer the money world and is generally seen as successful in the business and financial worlds. Warriors are adept investors, focused, decisive, and in control. Although Warriors will listen to advisers, they make their own decisions and rely on their own instincts and resources to guide them.

The Martyr

The Martyr is also one of the most common money types present in women. People of this type are often so busy taking care of others’ needs that they neglect their own. Financially speaking, Martyrs generally do more for others than they do for themselves. They often rescue others (a child, spouse, friend, partner) from some circumstance or other. They may even take on a higher-paying job that they don’t like, so others around them can live well.

The Fool

The Fool is a blend of the Warrior and Innocent money types – combining bold moves and risk taking without real thought about the true risks or consequences involved.

They typically have a strong desire for financial success, but resist doing the consistent, backend work to get there. A search for financial shortcuts such as lotto wins or ‘get rich quick’ schemes may be a part of their plan! They tend to be eternal optimists regardless of the circumstances and are more focused on the ‘here and now’ rather future outcomes.

Creator/Artist

Creator/Artists have a conflicted relationship with money, believing it undermines their desire to be on a more spiritual – less materialistic – path. This money type is often seen in creative entrepreneurs, spiritualists, non-profit employees, and people on a creative, artistic, or spiritual path. They love money for the freedom it buys them, but paradoxically, their negative beliefs about materialism act as a block to the freedom they so desire.

The Tyrant

Tyrants hoard money, and use it to control people, events, and circumstances. They may experience feelings of never being at peace with money, never having enough, and never feeling complete or comfortable with what they do have – even when they have an overabundance of money and all that you desire. Successful entrepreneurs often exhibit this type.

The Magician

The Magician is the ideal money type, exhibiting a spiritual-like awareness around the energy, the flow, and the deeper roles of money in their life. They are adept with their feelings and interactions with money, having previously become conscious of the patterns and behaviours preventing them having a healthy relationship with money. Magicians are confident they can create the financial reality they desire, growing money in ways that are aligned to their values.

OUR MONEY BEHAVIOURS AND ATTITUDES DRIVE OUR FINANCIAL – AND MENTAL – WELLBEING

Whilst there are many definitions of financial wellbeing, they typically all include some reference to the following components:

01 Able to meet financial commitments.

02 Have resources to enjoy life; and

03 Have an ability to cope with unexpected financial shocks

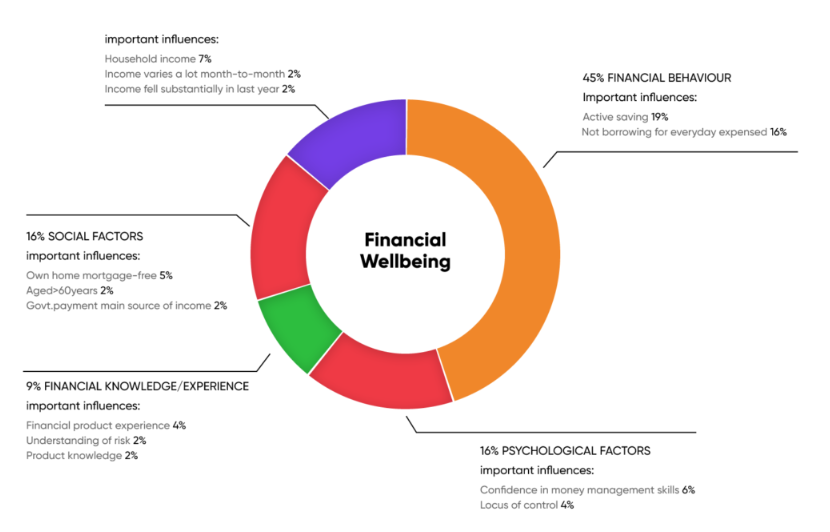

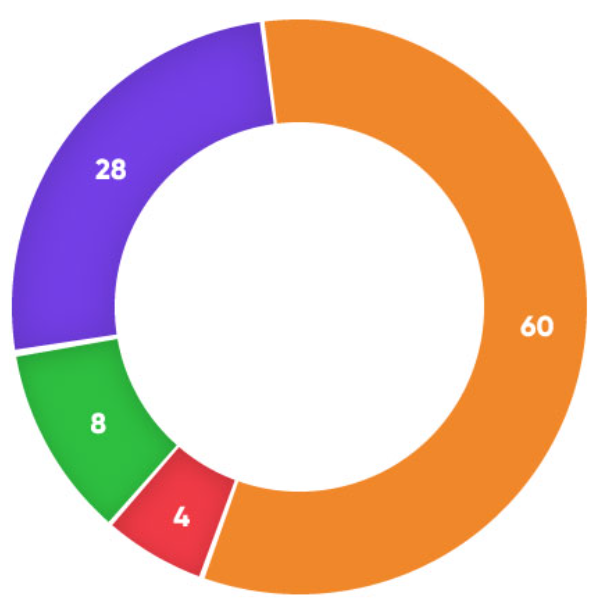

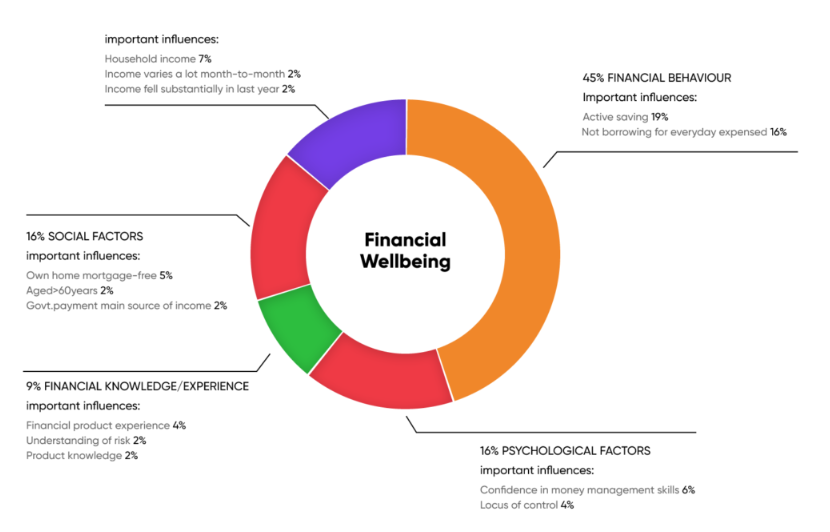

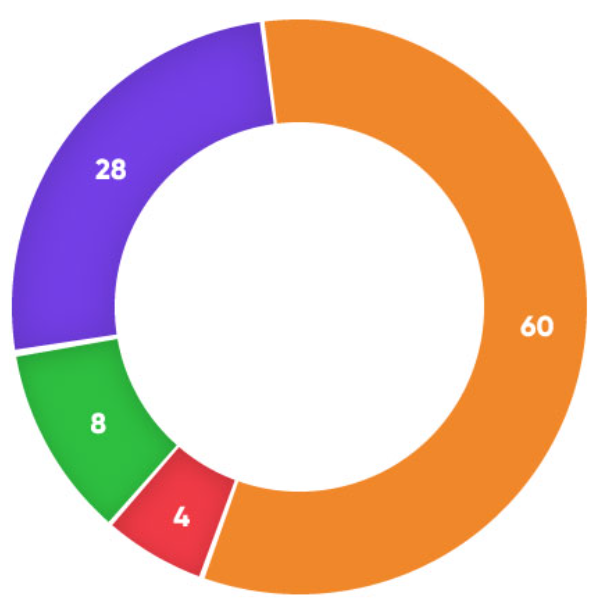

Extensive research has shown that behavioural and psychological factors are the biggest drivers of financial wellbeing, collectively explain around 60% of variations in financial wellbeing between individuals, whereas knowledge explained only 9% of variations 11.

FIGURE 2 DRIVERS OF FINANCIAL WELLBEING

Source: ANZ

UK researcher Elaine Kempson12 , whose work fed into the long running ANZ Financial Wellness survey, identified the key behaviours positively correlated with financial wellbeing as:

01 Planning expenditure against income

02 Prioritising spending on essentials

03 Disciplined spending

04 Living within means/not borrowing for essentials

05 Keeping track of money available for spending

06 Active saving

07 Planning for unexpected expenses or an income fall

08 Planning for retirement

09 Proactively seeking information and checking product features before buying a product

10 Gathering information before making a financial decision

References

08 Stress and Wellbeing, how Australians are Coping with Life, Stress and Wellbeing Survey 2015, Australian Psychological Society.

09 The New Psychology of Money, A. Furnham, Routledge, May 2014.

10 The Eight Money Types Defined, Money Coaching Institute, https://moneycoachinginstitute.com/eight-money-types/ , accessed July 2021.

11 Financial Wellbeing, A Survey of Adults in Australia, April 2018, ANZ Banking Group.

12 Financial Wellbeing, a conceptual model and preliminary analysis, E. Kempson, A. Finney & C. Poppe, Consumption Research Norway – SIFO, 2017.

Behavioural Advice Alpha

What kind of help are clients looking for?

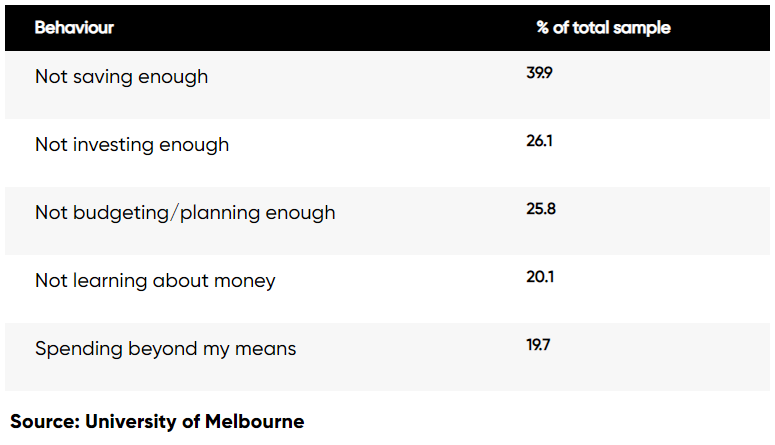

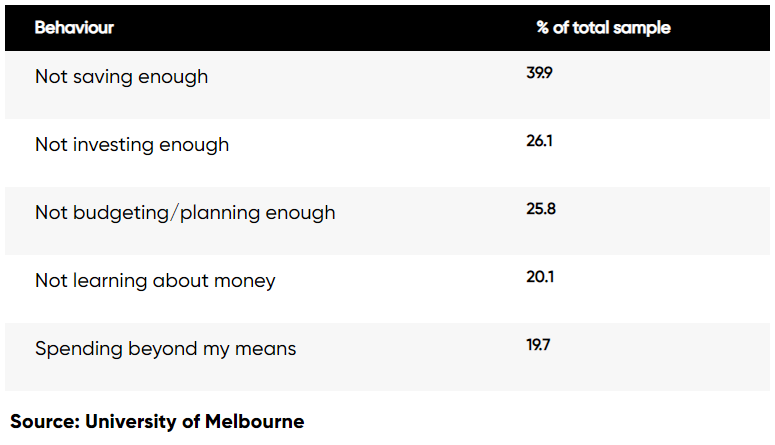

As replete with anxiety and bad money habits as Australians may be, we are at least self-aware. When respondents to a survey by the University of Melbourne13 were asked about their biggest financial regrets, the top 5 all related to the absence of behaviours known to be drivers of financial wellbeing, as mentioned above.

TABLE 3 BIGGEST FINANCIAL REGRETS

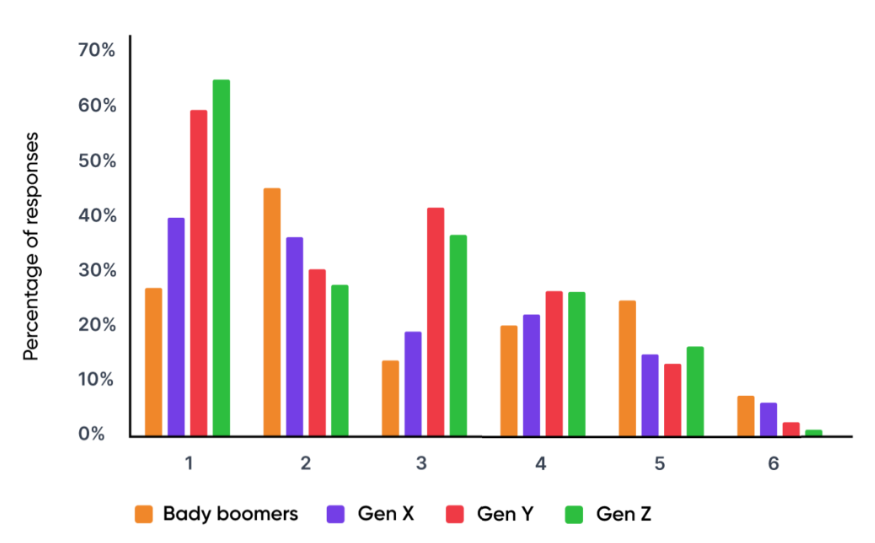

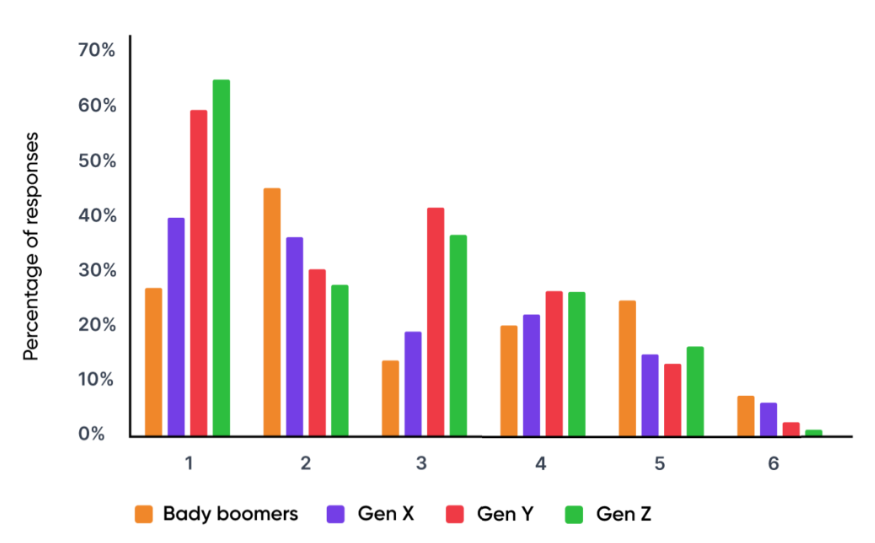

These findings are also consistent with ING/RiceWarner14 research which examined advice needs as self-identified by a cross-generational sample.

Figure 3 What advice would you/do you value more highly?

01 Budgeting and case flow management

02 Retirement Planning

03 Financial Coaching

04 Holistic Planning

05 Aged care support

06 Other

Amongst the key take outs for advisers from this research:

01 The demand for help with budgeting and cash flow management advice was strong across all generations

02 The demand for financial coaching was particularly strong for younger generations but was also appealing to around 1 in 5 Gen Xers.

To the extent neither of these services would currently be considered mainstream elements of the financial advice proposition and relate more to coaching and guiding than traditional product solution advice, this represents a significant unmet need amongst consumers, and an exciting opportunity for advisers.

Advice alpha and behavioural coaching

Numerous studies have sought to quantify the value of advice, usually in terms of extra wealth accumulated, tax saved, or investment performance improvements.

Coredata/AFA15 research proved beyond doubt advised clients generally pay less tax, have less bad debt, generate greater lifetime income, and earn a higher return on their investments.

In its recent ‘Future of Advice’ paper16 , the Financial Services Council highlighted its own 2011 findings that that the provision of savings advice would lead to an individual being between $29,000 and $91,000 better off at the point of retirement, as well as survey-based research conducted in 2014 that demonstrated that investors who received advice over:

01 The demand for help with budgeting and cash flow management advice was strong across all generations

02 The demand for financial coaching was particularly strong for younger generations but was also appealing to around 1 in 5 Gen Xers.

The value of behavioural coaching

A number of studies17 have concluded that behavioural coaching can add 1-2% net annual return to a client, around twice that attributed to asset allocation, and 6 times that from portfolio rebalancing.

The benefits of financial advice aren’t just financial

The FSC Future of Advice Report notes several studies which have observed the positive mental health benefit of financial advice.

These include the IOOF research18 which found those who receive ongoing financial advice experienced 13% greater levels of overall happiness, a 21% increase in peace of mind, and were 19% less likely to have arguments with loved ones.

Rather than this solely being an outcome of accumulating more wealth, however, it is clear that aspects of advice, and the advice process, trigger deep seated drivers of psychological wellbeing

According to Six factor model of Psychological Wellbeing19 , the drivers of psychological well-are autonomy, environmental mastery, personal growth, positive relations with others, purpose in life, and self-acceptance.

Two of these drivers in particular –environmental mastery and positive relationships – have strong alignment with the process and outcomes of financial advice.

FINANCIAL ADVICE INCREASES ENVIRONMENTAL MASTERY

A sense of control or mastery over one’s life is linked to improved mental health20,21 , including reduced anxiety and depression, increase resilience and enhanced life satisfaction and well-being.

A QUT study22 found, across multiple surveys, that the majority of clients viewed financial advice as making a positive contribution to a range of psychological well-being factors, including sense of sense of security, peace of mind and a sense of control.

FINANCIAL ADVICE BUILDS POSITIVE RELATIONSHIPS

Financial advice is built upon is trust-based relationships.

Discussing personal financial assets, personal life goals, and articulating plans for achieving those goals relies also relies on trust, candour, and a client’s willingness to be open and potentially vulnerable.

Clients who ordinarily wouldn’t dream of seeking out a counsellor or therapist will find themselves talking to their financial adviser about incredibly personal and emotionally charge topics such as a pending divorce, the aftermath of losing a loved one, caring for a special needs family member, or leaving a bequest.

Thus, financial advisers, whether they planned for it or not, may become personal coaches and counsellors for their clients, providing therapeutic value, perhaps without even realising it.

The extent to which Australian advisers are already having mentoring/counselling conversations with their clients is discussed in more detail later in this paper.

ADVICE PROCESSES ALSO DRIVE WELLBEING

Aspects of the financial planning process itself, including goal setting, and even regular reviews of progress, can also improve mental wellbeing.

SETTING GOALS MAKES US HAPPY

The setting and achieving of goals are at the heart of financial advice.

Research23 suggests that participating in activities aimed at developing goal setting can increase subjective well-being and personal growth over time (in particular, life satisfaction), either by bringing about changes in self-perception and/or self-confidence, or by positive changes in one’s circumstances. Planning for goals is also associated with a greater sense of control, and fulfilling plans underpins competence and capability.

REVIEW MEETINGS ALSO HAVE A WELLBEING EFFECT

While successfully achieving goals has a distinctly positive psychological effect, a positive mood state is also associated with the mere anticipation of future outcomes. In other words, just the perception of progress towards goals can provide a positive psychological boost, ahead of those goals being reached24. This suggests the regular client review process has a vital psychological benefit.

References

How Australians feel about their finances and financial services providers, C. Breidbach, C. Culnane, A. Godwin, C. Murawski & C. Sear, the University of Melbourne, Melbourne, 2019.

14 My Generation, behaviours and attitudes towards money, financial advice and retirement, ING and Rice Warner, January 2019.

15 Value of Advice 2018, Report published by Coredata and Association of Financial Advisers.

16 Future of Advice Report, Financial Services Council and Rice Warner, August 2020.

17 Putting a value on your value, quantifying Vanguard adviser’s alpha, Vanguard Research, March 2019.

18 The True Value of Advice Survey, IOOF, 2015.

19 Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological wellbeing, C. Ryff, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1989.

20 Daily psychological adjustment and planfulness of day-to-day behaviour, J.B. Nezlek, Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, vol.20, no.4, 2001.

21 Know thyself and become what you are: A eudemonic approach to psychological wellbeing, C. Ryff & B.H. Singer, Journal of Happiness Studies, vol.9, 2008.

22 The Value of Financial Planning Advice: Process and Outcome Effects on Consumer Well-being, C. Newton, S. Corones, K. Irving & D. Thomas, Queensland University of Technology Business School Research Project in Partnership with the Financial Services Council, 2015.

23 Personal goals and psychological growth: Testing an intervention to enhance goal attainment and personality integration, K.M. Sheldon, T. Kasser, K. Smith & T. Share, Journal of Personality, vol.70, no.1, 2002.

24 Increasing well-being through teaching goalsetting and planning skills: Results of a brief intervention, A.K. MacLeod, E. Coates & J. Hetherton, Journal of Happiness Studies, vol.9, 2008.

Being The Coach

Research shows advisers are already acting as coaches

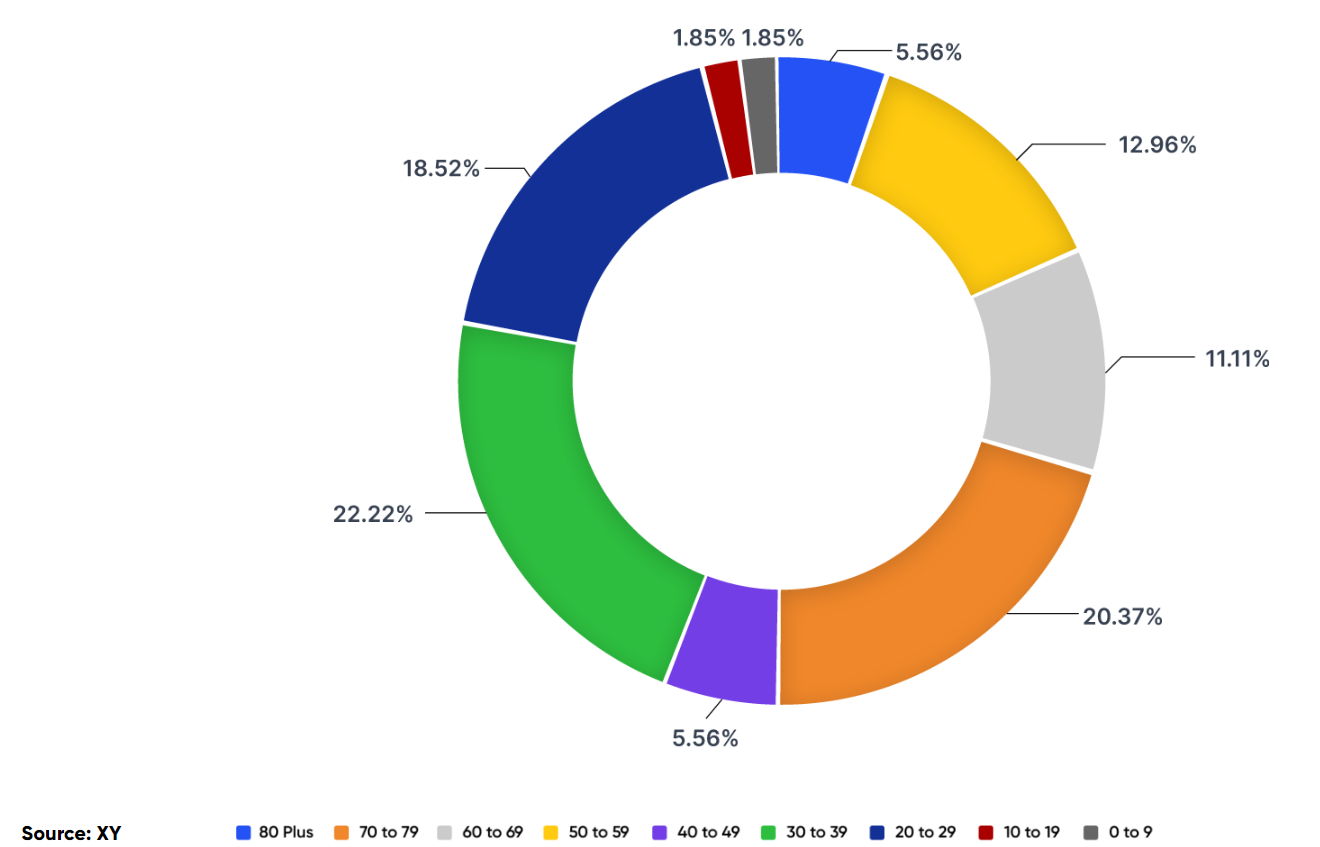

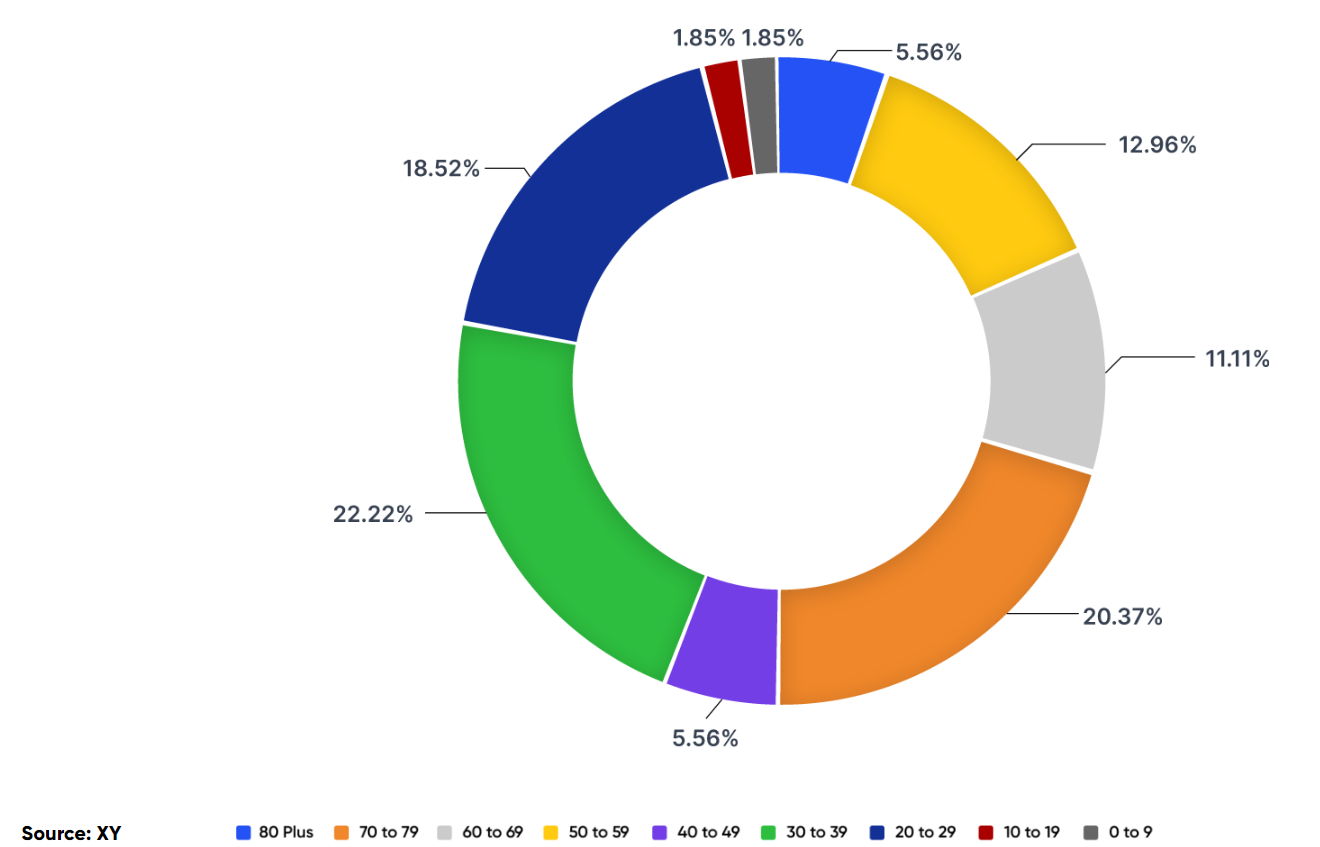

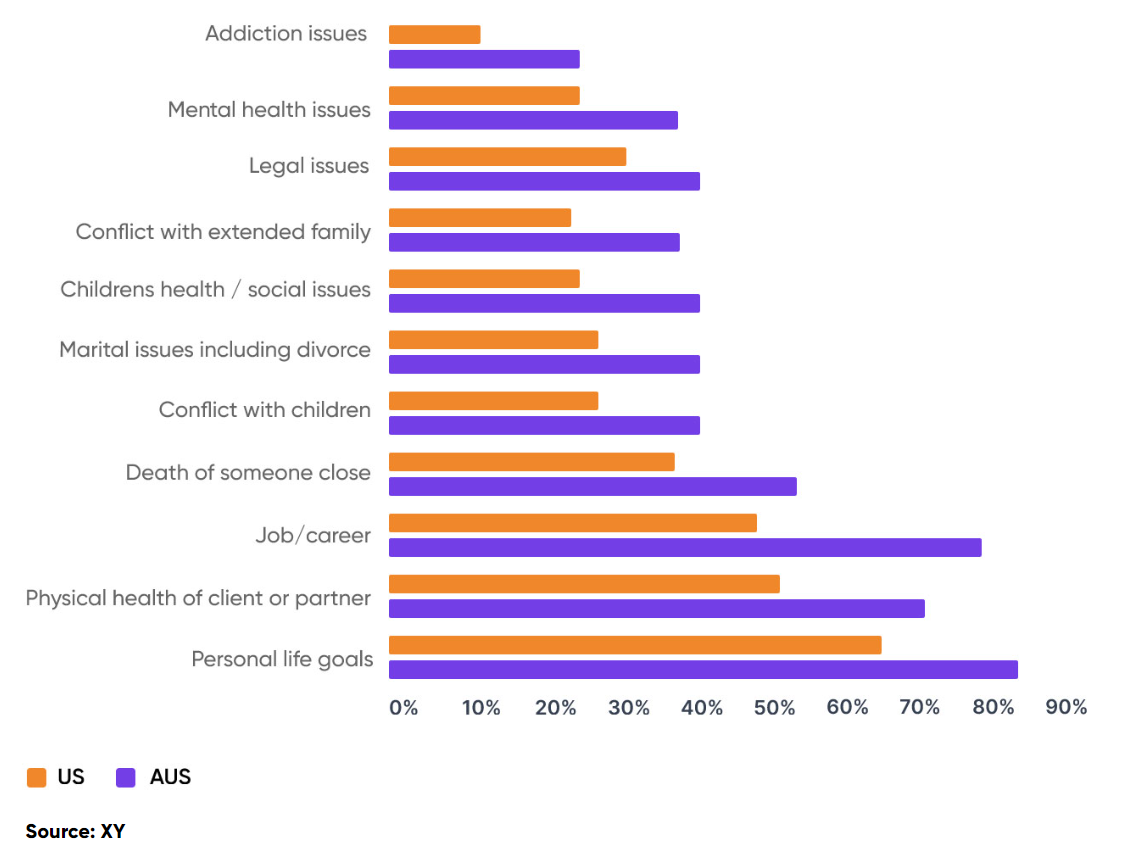

A survey of Australian financial advisers by XY25 provides a deep dive into the nature of conversations advisers have with their clients and examines adviser perceptions of the non-financial impact they have made on their clients’ lives.

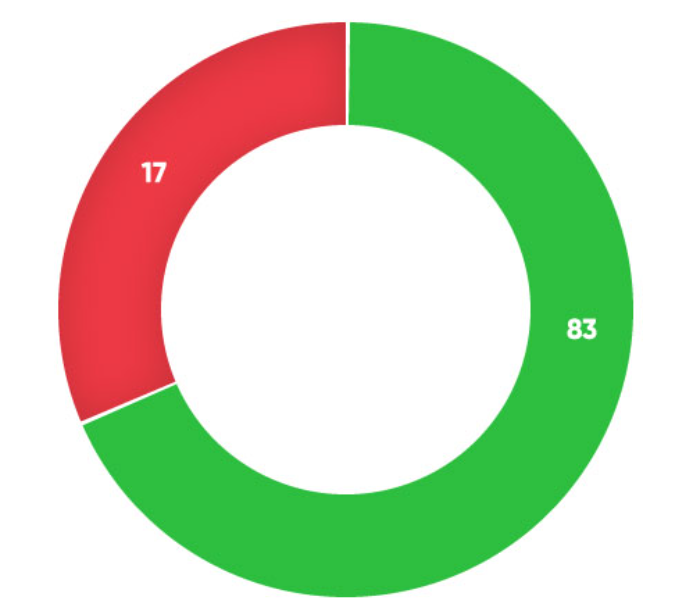

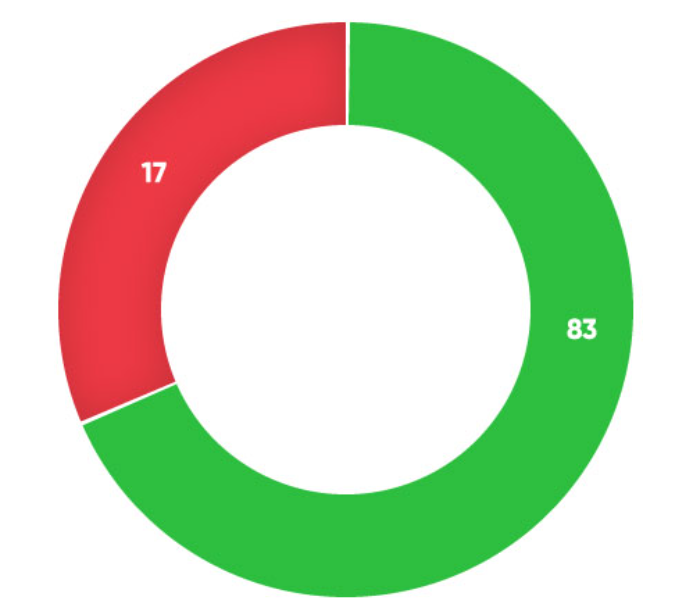

On average, Australian advisers spend 45% of their time with their clients talking about non-financial personal issues.

FIGURE 4 PERCENTAGE OF TIME SPENT DISCUSSING NON-FINANCIAL ISSUES WITH CLIENTS

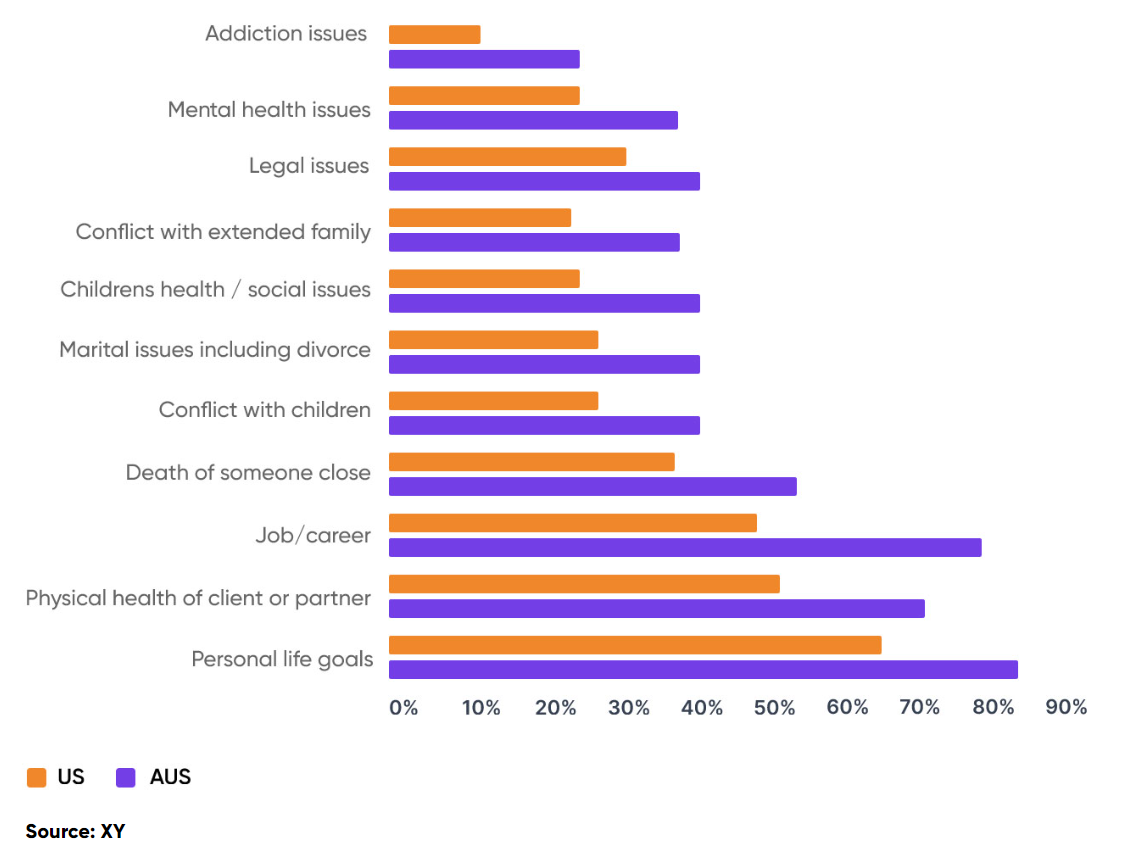

FIGURE 5 TYPES OF NON-FINANCIAL ISSUES RAISED BY CLIENTS

Percentage of clients raising issue

The impact of these personal, non-financial conversations

Advisers were asked about the impact these conversations had on their clients.

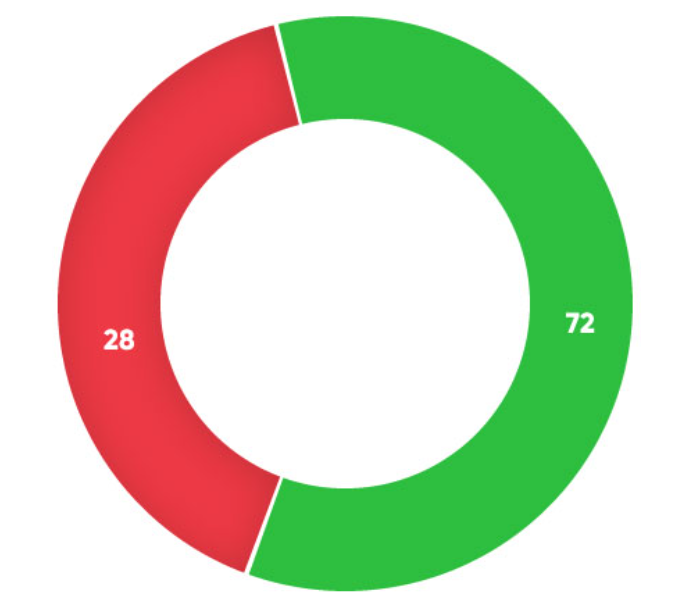

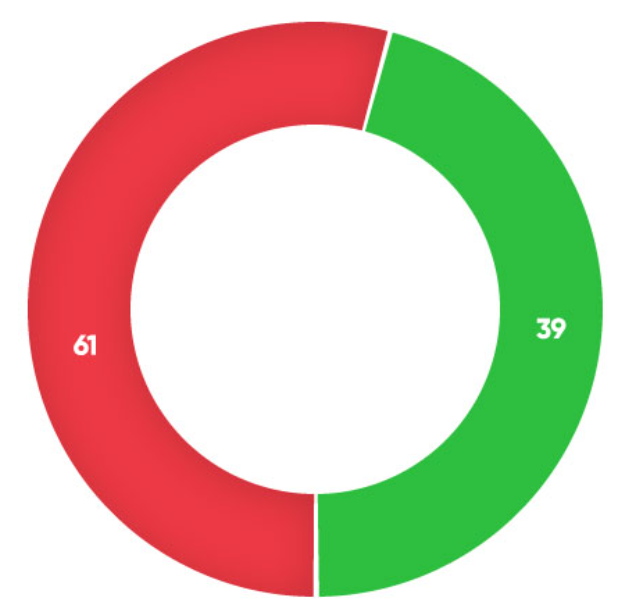

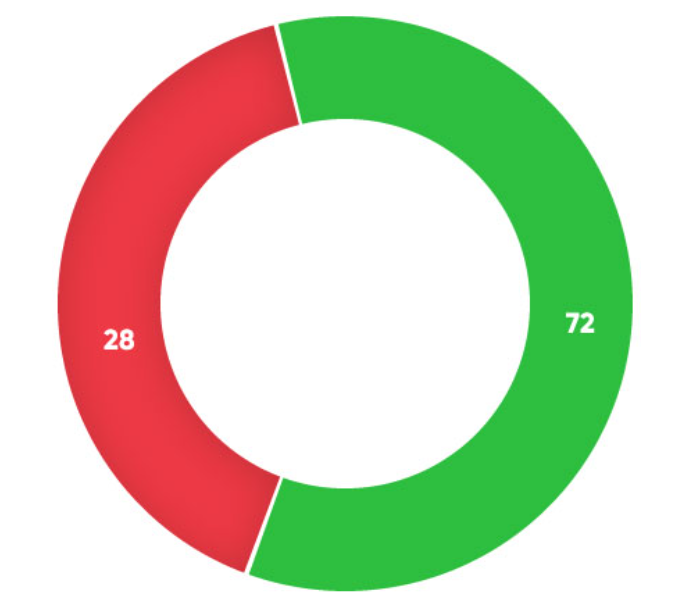

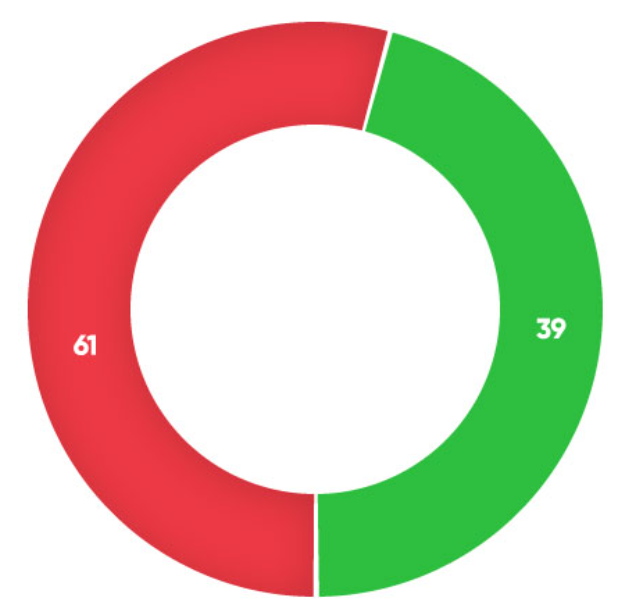

FIGURE 6 THERE IS MORE EFFECTIVE COMMUNICATION BETWEEN HUSBAND AND WIFE, PARENTS AND CHILDREN, OR OTHERS WHO MAY BE SIGNIFICANT IN MY CLIENTS’ LIVES.

FIGURE 7 THEY SEEM TO BE LIVING A LIFE CLOSER TO THEIR CORE VALUES, AND ENJOYING WHAT IS MOST IMPORTANT TO THEM.

Advisers as mentors and counsellors

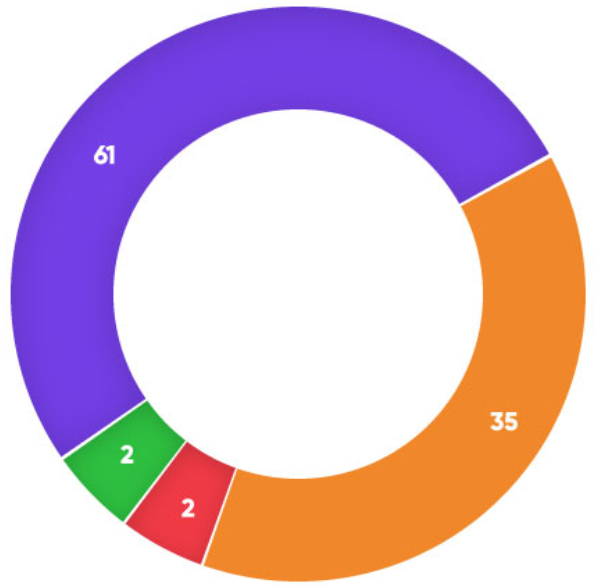

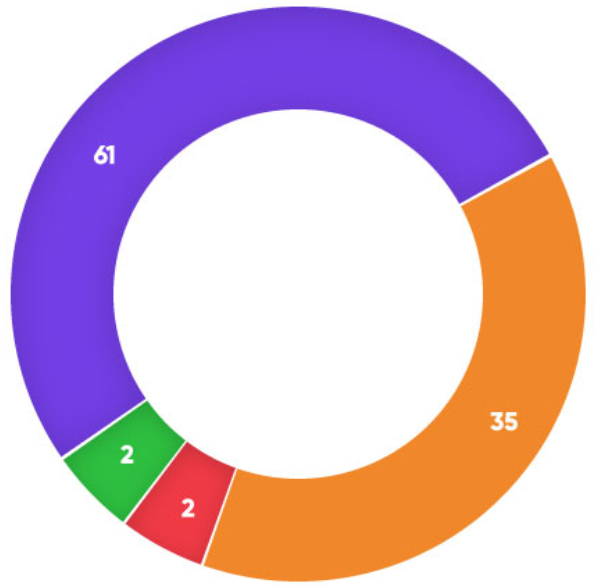

FIGURE 8 DURING A PLANNING SESSION YOUR CLIENT BECAME EMOTIONAL (CRYING, SOBBING, FEARFUL, ANGRY).

FIGURE 9 YOU WERE TOLD A SECRET BY YOUR CLIENT (WITH OTHER RELEVANT FINANCIAL FACTS), WHO SAID THAT YOU ARE THE ONLY PERSON WHO KNOWS THIS

FIGURE 10 YOU SERVED AS A MEDIATOR BETWEEN A FAMILY OR EXTENDED FAMILY MEMBERS

FIGURE 11 YOUR CLIENT DESIGNATED YOU AS THE PERSON TO CONTACT IN THE EVENT OF AN EMERGENCY

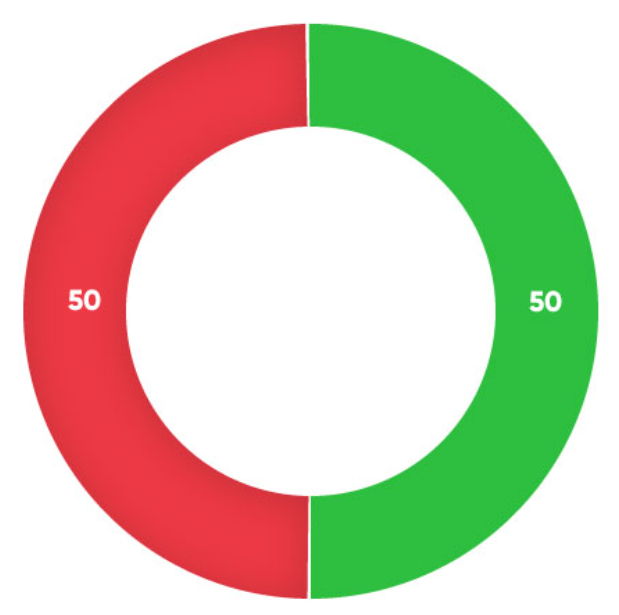

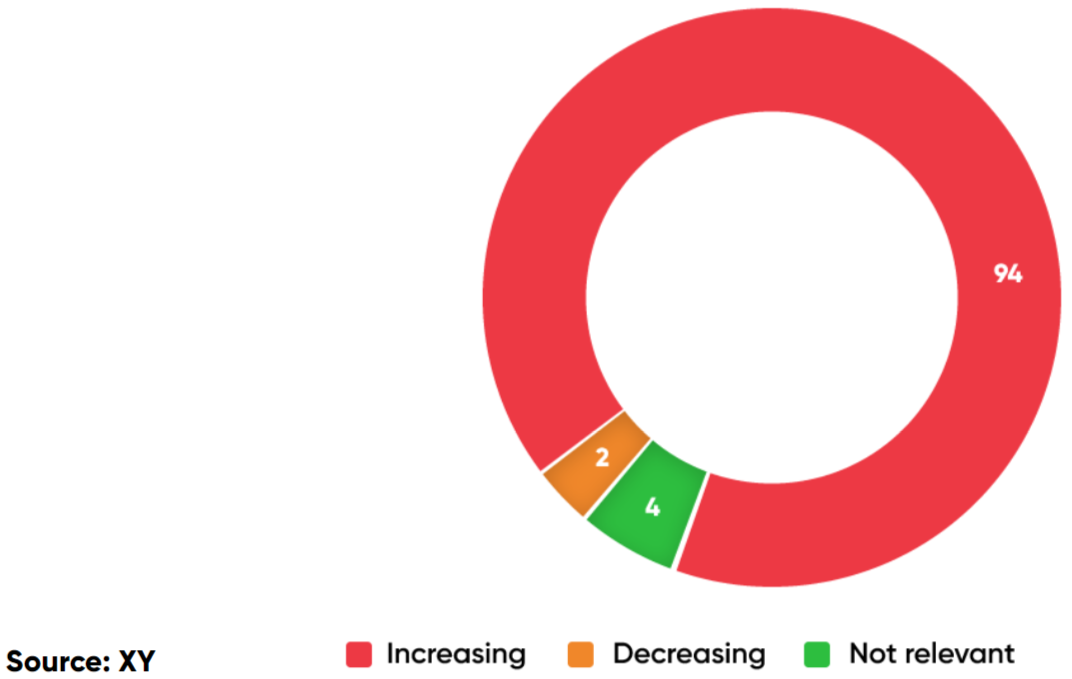

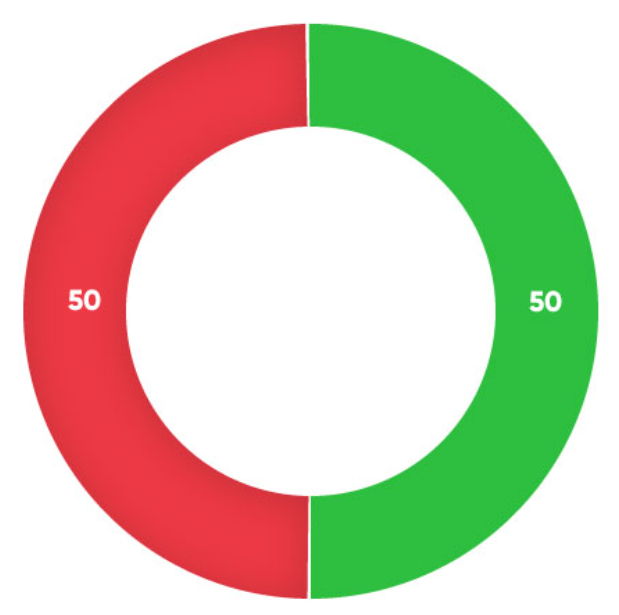

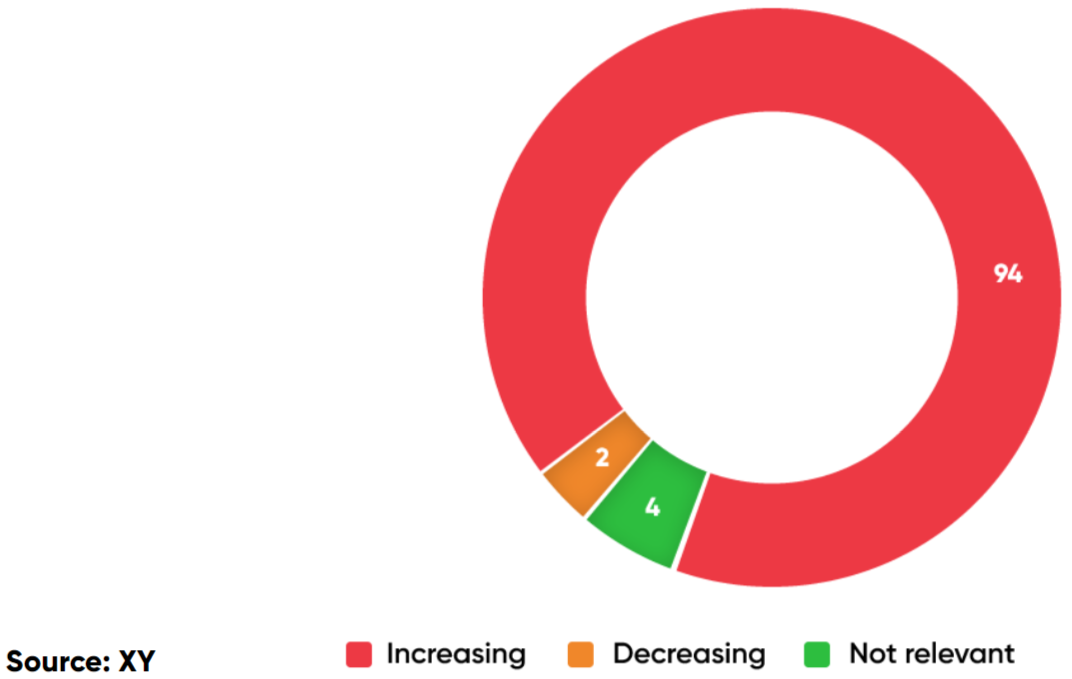

FIGURE 12 TO WHAT EXTENT DO YOU PERCEIVE YOUR ROLE AS A COACH AND COUNSELLOR INCREASING OR DECREASING IN IMPORTANCE?

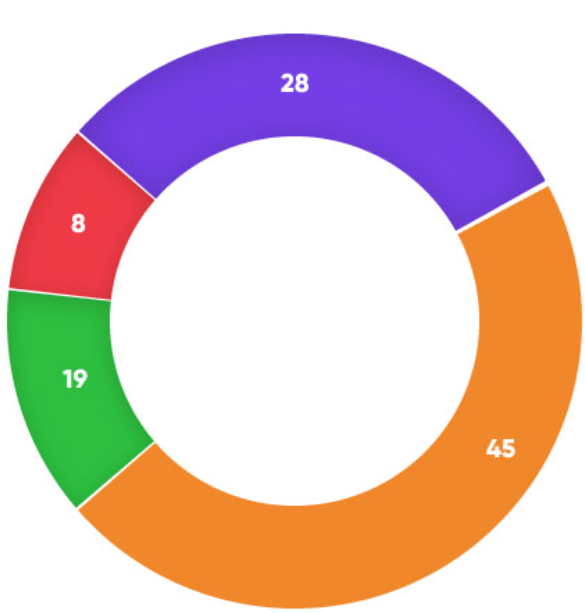

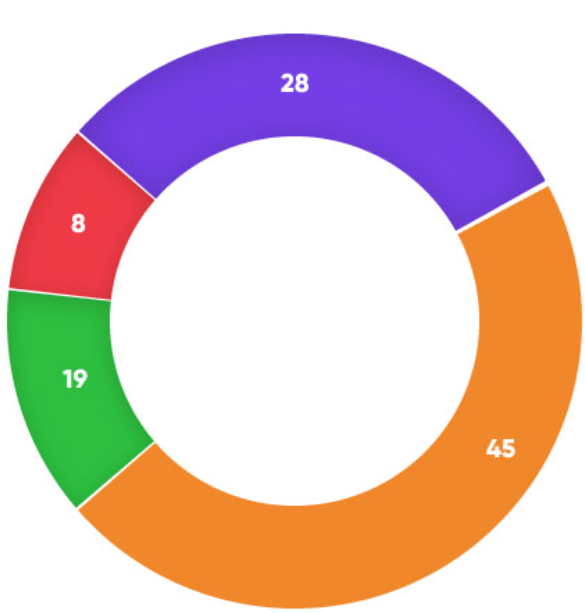

Business impact from acting as coach and counsellor

FIGURE 13 MY ABILITY TO DO A GOOD JOB AT FINANCIAL PLANNING IS ENHANCED OR IMPROVED

FIGURE 14 MY BUSINESS HAS INCREASED

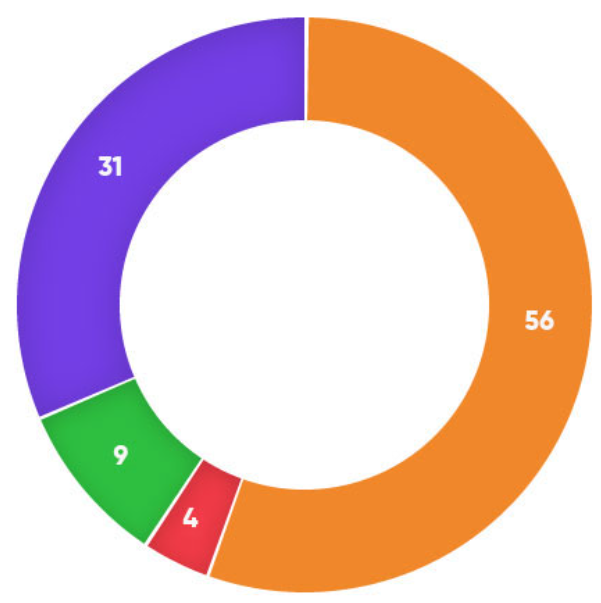

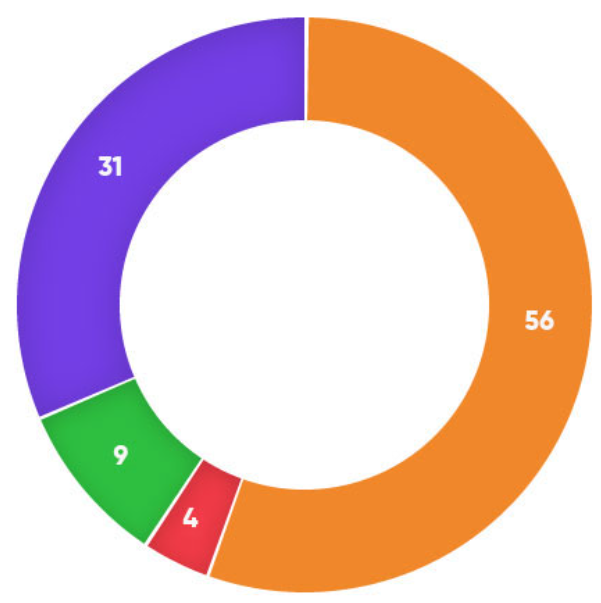

94% of advisers expect their role as coach and counsellor to increase in importance

Formally implementing a coaching approach

It is abundantly clear that financial advisers provide more than just financial expertise. For the majority of clients, the adviser is also a mentor, counsellor and mediator, providing support as their clients live out the human drama of day-to-day life.

Advisers are therefore already well positioned to more formally offering coaching as a service. And the consumer demand is clear.

For advisers considering this path, there are a number of considerations, including how advice processes may need to change, how to charge clients for coaching, and skills and training requirements.

Illustrative coaching-based process

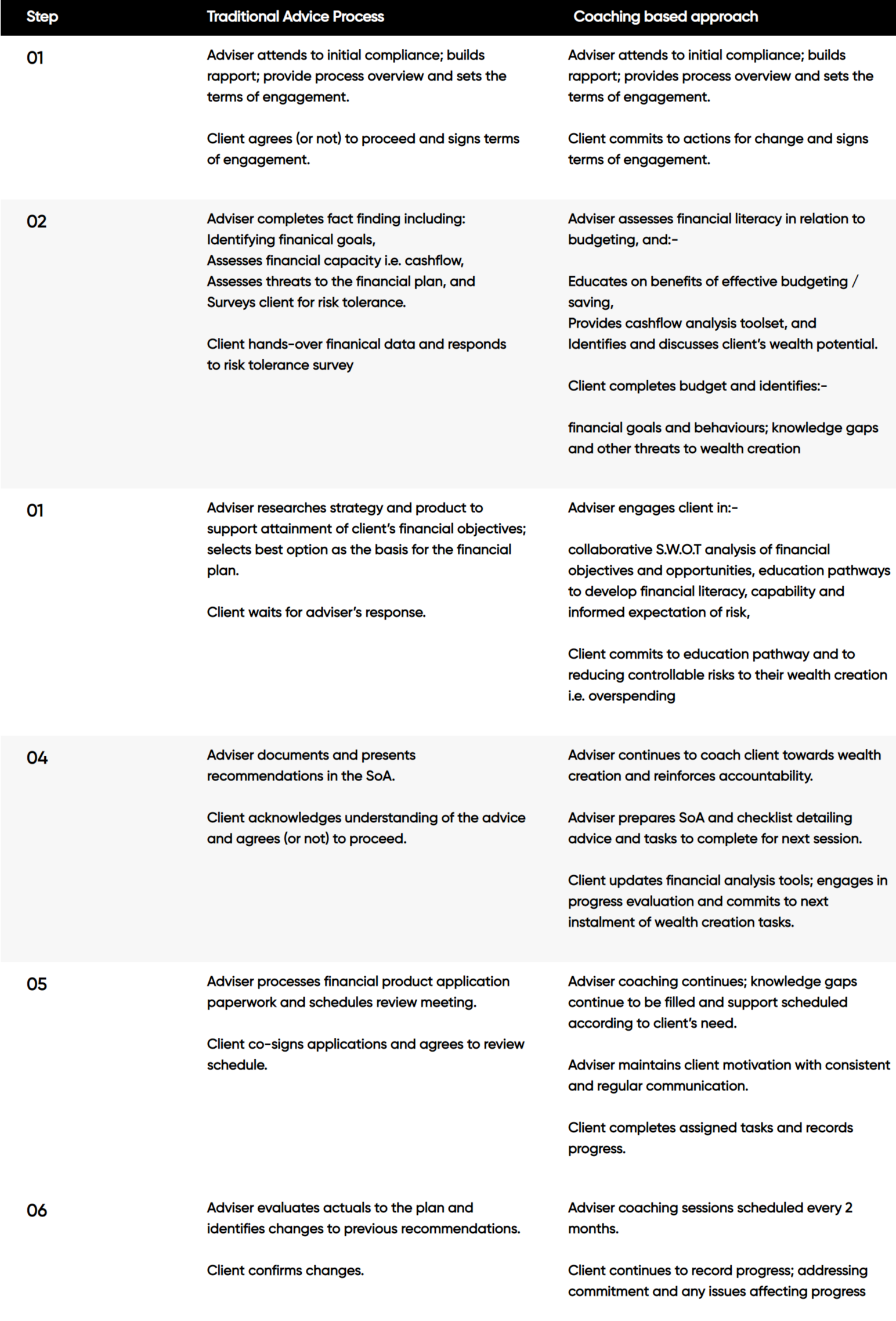

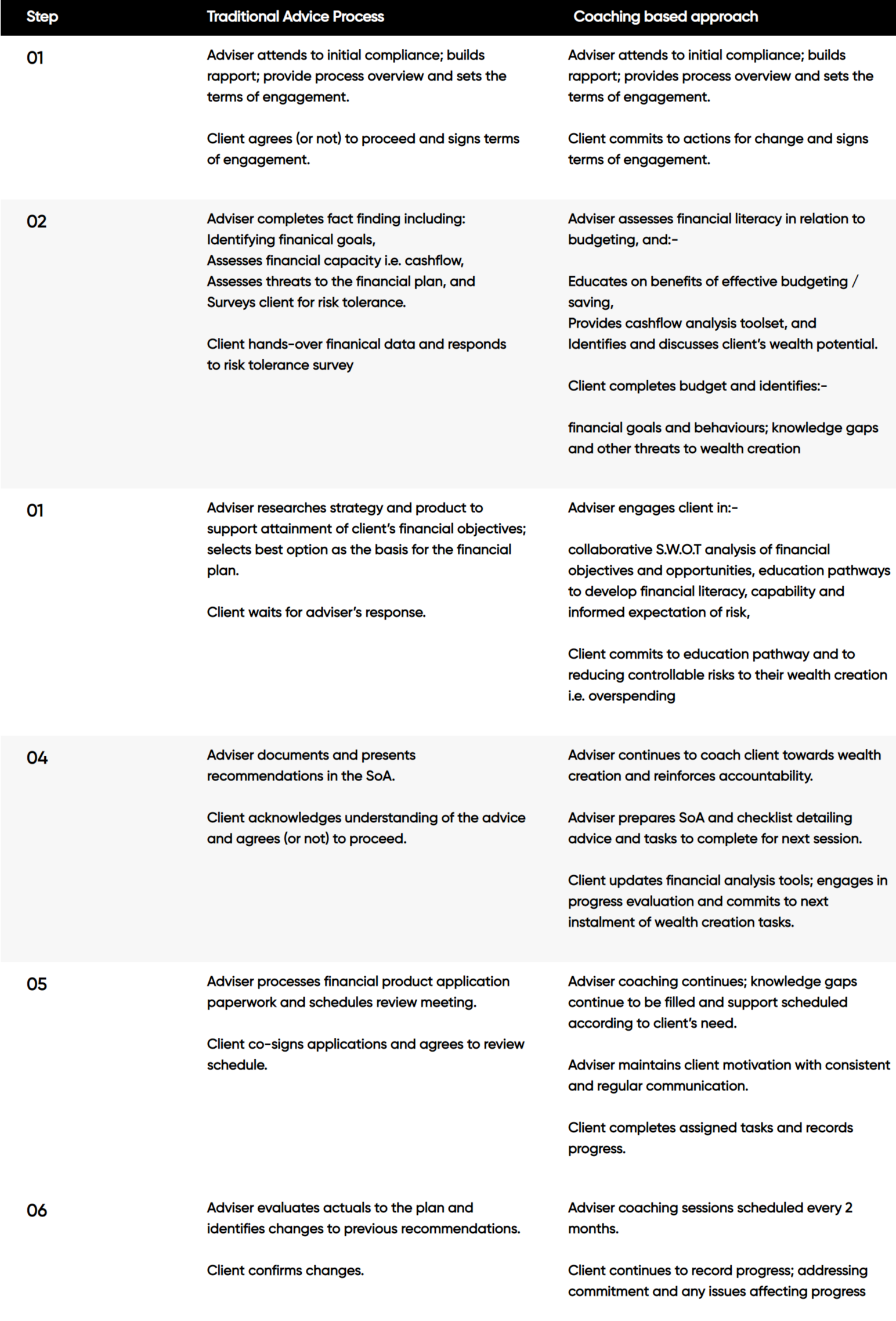

How would a coaching based advice process compare with a standard advice process?

A Griffith University Study26on financial coaching compared the standard six step planning oriented advice process with a coaching oriented process, as shown below.

Table 4: Coaching v traditional advice processes

Source: Griffith University

Of course, if coaching doesn’t involve any personal advice (and often it doesn’t need to), then the process can be much simpler and more cost effective.

References

25 XY Survey of Australian Financial Advisers, August 2020.

26 The Financial Coaching Advice Model: An exploration into how it satisfies expectations of quality advice, J. Knutsen and R. Cameron, Griffith University, Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, Volume 6, Issue 4, 2012.

Start Implementing Now

Compounding our money beliefs are our decision-making flaws

Skills and training required

When you break down financial coaching to its essence, it becomes obvious that advisers are already well placed, by way of skills and experience, to coach their clients:

ESSENCE OF FINANCIAL COACHING

01 Educate clients in sound financial principles

02 Assist clients in the process of overcoming financial indebtedness

03 Hep clients identify and modify ineffective money management behaviours

04 Guide clients in developing strategies for achieving financial goals

05 Support clients as they work through their financial challenges and opportunities

06 Help clients develop new perspectives on the dynamics of money in relation to family, friends, and self-esteem.

For Australian financial advisers there are no additional qualifications or accreditations required to be a financial coach. Satisfying the training, licensing and education requirements to act as a registered financial adviser is sufficient.

Nor does coaching require any formal training in mental health, or psychology.

Advisers are already qualified to provide guidance on financial matters. Learning to identify and adjust the approach for individual client money attitudes, behaviours, and cognitive biases requires more of the soft skills we often talk about – communication, empathetic listening, message emotional intelligence. Successful advisers typically have these skills in abundance.

Being remunerated as a coach – the question of fees

One of the more exciting aspects of incorporating a coaching service within your advice offering is it creates the opportunity to generate fee-based revenue from a broader range of clients – clients who may not yet have the assets or complex situation to be viable under a traditional advice approach.

A client who is savings hundreds of dollars per month because of your coaching will be willing, and able, to pay a fee for that help.

There are a variety of approaches advisers could take to setting coaching fees. Importantly, if it is to be offered as a standalone service, it needs to be priced accordingly (not as a loss leader or bundled in with product or asset-based remuneration).

One approach is based on a fixed period of engagement—e.g., $2,500 for a six-month program. Another is a monthly retainer option, or per hour/single session options. Charging on the basis of savings achieved is another option, the value of which is clear to the client.

Group coaching can also be a very effective and efficient way to deliver coaching to fee paying clients.

If coaching takes the form of specific assistance around budgeting and cash flow, there are a number of options here too. Firms already in this space are experimenting with different pricing models, designed to balance affordability and value with sustainability.

MODELS BEING EXPLORED ACROSS THE MARKET INCLUDE:

01 Offering short, digital courses on the fundamentals of cash flow and budgeting for a small fee (e.g., the ‘She’s on the Money’ Budgeting and Cash Flow Masterclass)

02 Tiered models with differentiated fees and services

03 Month to month subscription services with flexible packagess

04 Upfront set-up fee plus small monthly or annual fee alongside existing advice feess

The advantages of a coaching based approach

Whether a coaching offering includes specific help around cash flow and budgeting, or is more geared around improving money attitudes generally, there are many advantages to firms who embed such an approach in their offering:

01 It opens up a broader target market, not traditionally seen as viable for advice

- Younger clients

- Clients with few assets

- Clients who want to take a DIY approach to investing but need some guidance

02 It creates a bigger advice pipeline

03 It helps demystify financial advice and makes it more approachable and accessible

04 It makes the value of advice more obvious

05 It is a high value add service that differentiates the firm from others

06 It allows firms to charge stand-alone advice fees more confidently, to clients who are more willing to pay them

07 By improving the money behaviours of clients, advice outcomes can be optimised

08 An advice offering which resonates emotionally – not just functionally – with clients, creates deeper engagement, greater customer satisfaction and increased client loyalty

AN ADVICE OFFERING WHICH RESONATES EMOTIONALLY – NOT JUST FUNCTIONALLY – WITH CLIENTS, CREATES DEEPER ENGAGEMENT, GREATER CUSTOMER SATISFACTION AND INCREASED CLIENT LOYALTY