Portfolio construction: avoiding bad behaviour

A new era approach to defining and aligning risks to individual investment goals

In this special production

About this paper

This paper is a companion to the Ensombl podcast series ‘Behavioural Investing’.

We would like to thank the following advisor/expert contributors:

Introduction

Now more than ever, successful investing is challenging. Investors are constantly required to make high stakes decisions on the basis of increasing amounts of complex, and sometimes conflicting data and signals. Gathering, processing, then distilling all this data to allow timely, accurate decision making can be hard enough for professional investors, let alone individual ‘mums and dads’.

As with all aspects of our lives, when faced with information overload, we rely on mental shortcuts – biases – to help us stay on top of all the decisions we must make each day. But when these biases come into play with our investment decision making, the results can be bad behaviours, and outcomes that have a lasting impact on our financial wellbeing.

The Ensombl Podcast series ‘Behavioural Investing’, addressed this very topic, and concluded that, by grounding investment goals in a client’s personal values, better aligning individual goals with variable and evolving risk tolerances, and constructing differentiated portfolios to reflect these goals and risk tolerances, advisors can create more client ownership and understanding of the investment strategy used for each goal, thereby avoiding surprises, and minimising the likelihood of value destructive behaviour.

Produced as a companion to the Behavioural Investing series, this paper explores the outcomes of the poor investment behaviour that our biases can drive, and examines the ways advisors can better connect values, goals, and risk, to drive better advice outcomes.

We are bad decision makers

As human beings, we make a lot of decisions, around 2,000 every hour according to research1.

Many of them are low level, unconscious decisions of little consequence, what to wear, what to eat, which route to take to work. But some of them are more serious, even life changing decisions about our relationships, careers, and investments.

Yet despite how practiced we are at decision makers, most of us are notoriously bad at them, straying away from the rational, fact-based frameworks of text-books, and instead being influenced by a range of factors, including our emotions, our biases, and our mental bandwidth.

One of the most famous studies2 on this topic found that prisoners are more likely to be given parole in the morning, than when their cases are heard in the afternoon (when judges’ energy levels start to wane).

Expert Insights – objective decision making is hard

“If you look at the data and research, it shows none of us are particularly good decision makers. Even paid, professional decision makers such as judges, struggle to make consistently make sound, truly objective decisions.” Katherine Hunt.

“Having that third party available to help you with decisions, is one of the main reasons I think that people actually seek a financial advisor to help them. There are some things they may be able to do themselves, if they had the self-control, the attention to detail and the ability to detach, but they can’t [always do this], because we are human.” Patricia Garcia

One of the biggest drivers of our poor-decision making ability is sheer mental overload, and the short cuts we must rely on to make the volume of decisions necessary to get us through the day. Scientists estimate the human body sends 11 million bits per second to the brain for processing, yet the conscious mind can only process around 50 bits per second3.

And the mental load is only increasing.

Scientists estimate we process at least 5 times more information today than we did in 40 years ago4. The digital age may have its upside, but it also creates a state of almost constant distraction and struggle to focus.

We cope by using shortcuts

The only way we can cope is to use mental short cuts (heuristics) to make decisions amongst this deluge of data. These are our behavioural biases.

As helpful as these mental shortcuts are, they can contribute to poor decisions and poor behaviours. And those poor decisions and behaviours can come at a cost, especially when they relate to our investing.

Expert insight – biases help us avoid decision overload

“Whenever we use emotion to make decisions, that can develop into a behavioural bias. But it isn’t necessarily a bad thing. If we didn’t use our emotion to make decisions, our brain, our tiny little primate brain would be so overloaded, we’d just curl ourselves into a bundle on the floor. They key is to recognise when biases are at play.” Katherine Hunt

The cost of behaving badly

Amateur investors, reliant purely on their own resources, make poor decisions, and those decisions can come at the cost of consistent underperformance.

One of the longest running and most comprehensive studies on this topic is the Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behaviour (QAIB) report, published annually by investment research firm Dalbar.

Their report for the 30-year period ended 31 December 2022 – a period including the tech crash, the GFC, September 11, COVID, and the brutal 2022 – found that while the S&P 500 posted an average annual return of 9.65% for that period, the average U.S. equity mutual fund investor achieved an average annual return of only 6.81%, around 30% lower than the market5.

Take out the Covid recovery of 2020 – when the irrationality of retail investors actually worked in their favour – and the underperformance gap was even more stark.

JP Morgan data for the 2001 – 2020 period found the average US investor achieved an average annual return of just 2.9%, compared to the 7.5% pa achieved by the S&P 500 over the same period6.

Approaching the issue from a different angle, a study by Russell quantified the performance uplift from advisors coaching their clients to make better decisions.

In their 2023 Value of an Advisor Report, Russell estimated behavioural coaching by financial advisors could improve the performance of client’s portfolios by as much as 3.4% per annum7.

The behavioural gap

The gap between the performance of an investment, and the performance achieved by an individual holding that investment, is called the behavioural gap.

This gap has become the subject of countless studies, research papers, and even best-selling books (including ‘The Behaviour Gap’) by US base financial advisor and investor educator, Carl Richards8.

Morningstar analysis of several investments have found the gap can range from 25% to 50% or even more9.

And at the heart of the behaviours driving this gap can be found that bundle of complex, deep-seated, often unconscious mental short cuts we call biases.

The cognitive and emotional biases that drive investor behaviour

As mentioned above, the only way we can cope with the vast amounts of data and decisions we must process each day is to use mental short cuts. These shortcuts look for patterns, make associations and quick inferences based on the limited information we can digest. These are our behavioural biases, and there are generally two types:

• Emotional biases

Emotional biases are often spontaneous, and influenced by the way we feel at the time of making a decision. They can be deeply rooted in personal experiences; and

• Cognitive biases

Cognitive biases can be thought of as ‘rules of thumb’, or decision making according to an established framework, that may or may not be grounded in fact.

Common emotional biases

Loss Aversion

Loss Aversion is one of the most common biases impacting our investment decisions.

Simplistically, loss aversion means that individuals feel the pain of a financial loss far more than they enjoy a financial gain of equal value. According to Nobel Prize winning economists Kahneman and Tverskyy10, for any given amount, losses hurt twice as much as a gain of the same amount.

In an investment context, the fear of losses can lead to three sub-optimal behaviours:

• Avoiding risk, which can see clients adopting an overly conservative investment approach, incapable of delivering the returns needed to achieve their goals & objectives

• Selling assets at the worst time possible (during a downturn)

• Holding onto investments that should be disposed of, purely to avoid a loss.

Overconfidence

Sometimes investors overestimate their own abilities, believing that they are smarter or more informed than they really are. Associated effects can include poor stock selection, increased risk taking, and more frequent trading of stocks, all of which can drag down portfolio performance. Various studies have shown men are more likely to exhibit overconfidence than women.

Status Quo bias

As humans we can be highly resistant to change, and our response to new circumstances can often be to do nothing. This bias might see an investor reluctant to research new ideas or invest in new stocks or sectors, instead coming back to the same investments we have had before, perhaps telling ourselves ‘We understand them more’. Limiting one’s horizons can limit the potential for profit.

Endowment effect

The endowment effect sees us assigning a disproportionately high value to what we already own. Similar to loss aversion, it can see us hold onto investments too long, when others in the same sector may be a better opportunity.

Present bias

The present bias refers to the tendency of people to give stronger weight to payoffs that are closer to the present time when considering trade-offs between two future moments. It’s the reason many people are terrible at saving over the longer term. The ubiquity and strength of this bias is the reason policy makers introduced compulsory superannuation.

Expert insights – biases are evident with all clients

“ I see present bias a lot, but then I also see clients at the opposite end of the spectrum. I know the signs and can tell who is a ‘today client’ and who is a ‘tomorrow client’. Being totally focused on tomorrow isn’t necessarily good, if it means forgoing quality of life, and there’s certainly some retiree clients who I need to remind to spend and enjoy life a bit more right now. My job is an advisor is to help them become a bit more balanced.” Patricia Garcia

“What can be especially challenging is when you are advising a couple, and each has a different degree of present bias. Some sort of negotiation process then becomes crucial”. Katherine Hunt

“Superannuation is really a big nudge which accounts for a number of behavioural biases. If you left that choice to the individual, people would struggle to put 10% of their savings aside for 40 or so years.” David Bell

“I think some clients mislabel themselves as having a bias towards a certain type of behaviour, so they will tell you ‘I’m a spender, I’m a saver, I’m a conservative investor’. And then you dig deeper and find it’s not necessarily true”. Antoinette Mullins

Common cognitive biases

Anchoring

The anchoring bias causes us to rely heavily on the first piece of information we are given about a topic. When we are setting plans or making estimates about something, we interpret newer information from the reference point of our anchor instead of seeing it objectively.

In a broader context, investors can also be anchored around other reference points, including individual stocks, regions, performance benchmarks, and even individual CEOs, all of which can undermine objective decision making.

Expert insights – anchoring is seen in many forms

“Anchoring is like having a rule of thumb. Anchoring around past performance is a common behaviour, but I’ve also seen some investors anchor around their favourite companies, but also individual CEOS and portfolio managers.” David Bell

“Anchoring on the basis of historical experiences is understandable, and some clients will already have their favourites before they even see an advisor. A love of residential real estate is a common anchoring point, especially amongst investors who were burnt by equity markets during the GFC. Understanding why a client is anchored this way can help an advisor target their education and communication.” Dan Miles

“Because so many people have industry super funds holding both their retirement savings and insurance, they can often be a good reference point to anchor the advice conversation around. Recommendations can be framed in the ways they are similar, or different to what they already have and understand, if only at a basic level.” Antoinette Mullins

Gamblers Fallacy

The gambler’s fallacy describes our belief that the probability of a random event occurring in the future is influenced by previous instances of that type of event. Believing markets are due for an ‘up day’ or even an ‘up year’ purely on the basis of successive down periods is a pertinent example of gambler’s fallacy.

Confirmation bias

People tend to seek out evidence and opinions that confirm their existing beliefs, ignoring other information that challenges or contradicts their views. Once we have decided we like an investment, we are likely to place more weight on the research and commentary that supports our ‘thesis’, than on dissenting voices.

The bandwagon effect

Going with the herd can often make us feel safe, but in an investment context it can be problematic. This bias explains the tendency of investors to chase returns, often arriving at an opportunity when most of the growth has already occurred.

The bandwagon effect works in both directions, hence Warren Buffet’s advice to ‘be greedy when others are fearful, and fearful when others are greedy’11.

Availability bias

The availability bias sees investors base decisions on information and experiences that most readily come to mind. This can be information that is currently in the news, or it could be based on previous, deeply felt experiences. An investor who has previously made significant losses in a particular investment type may remain ‘scarred’ and look to avoid those investments in the future, even if the factors behind those losses are known and avoidable.

Expert insights – biases aren’t always bad

“One bias which attracts a fair bit of criticism from academics is mental accounting, or bucketing. The truth is, most people think in terms of different money buckets, each with its own usage and timeframe. Subconsciously we apply different risk tolerances to those buckets, which is actually a principle that can be applied effectively to investment portfolios and retirement savings. Biases don’t have to be value destructive, they can be value accretive, but recognising their existence and adapting your approach is critical.” Dan Miles.

“The disposition effect is a bias which explains why people tend to sell assets that have increased in value and keep assets that have fallen in value. While that might sound sensible, it can be counterproductive when it means cashing out of winners too early, and hanging onto losers too long, just because we can’t accept that we have made a loss. That’s where investment committees can be helpful, providing an objective free assessment, without emotion, telling you to get out of a position.” David Bell.

Mitigating biases and overcoming bad behaviour

As already mentioned, financial advisors can and do play a vital role in coaching/mentoring their clients to help them make better decisions and avoid value destructive behaviours.

But the sheer volume of decisions individual investors need to make, and the abundant opportunities for bad behaviours, make it impractical for advisers to provide this decision support on a one to one, case by case basis.

Creating better investment behaviours among clients requires advisors to use a framework that is robust, repeatable, and scalable.

Best practice analysis identified three key elements in such a framework:

• Aligning and prioritising investment goals around client values

• The application of risk benchmarks that better reflect client behaviours and market dynamics and are tailored to individual goals; and

• Client financial literacy.

Aligning client values and goals

Goals are a fundamental pillar of financial advice.

Advice recommendations are framed through the lens of achieving a particular client goal. Those recommendations will include the actions required to move closer to those goals, which may involve spending and lifestyle changes, taking out insurance coverage, or investing.

Most clients are largely oblivious to the technicalities of investment markets, tax, and Centrelink, and their sole focus is the achievement of their goals. The only performance benchmarks relevant are whether they are closer to, or further away from, achieving their goals. The emotional uplift they get from seeing progress towards their goals can be extremely powerful, and is indeed often overlooked as one of the true sources of value clients see in financial advice.

It can often be tempting to define client goals in functional, financial terms:

• Achieve an income of $xx in retirement

• Be able to take one overseas trip per year

• Fund my grandchildren through private school

However, framing goals purely in functional terms can often mean the emotional link between a client and a goal is overlooked or minimised. Without this emotional link reminding clients why they are following a particular course of action (such as paying for insurance cover or investing in a particular way), they will be more easily knocked off course when conditions become challenging, for example if their portfolio suffers volatility and/or losses.

Expert insight – the power of visualising goal achievement

“Technology can play a big role in helping clients visualise their goals. One memorable example was the technology that projected your savings outcomes based on your current trajectory, and in conjunction with a real estate website, showed you the type of property you could afford to live in based on current behaviour, and where you could live if you upped your savings.” David Bell

Expert insight – clients aren’t always sure why something is so important to them

“You often have to dig into the foundations of their goals. They might want to be debt free, but you need to find out why that is so important to them. Is it about freedom? Is it about fear? Sometimes clients don’t know exactly why something is important to them and you need to help them unravel things.” Antoinette Mullins

Grounding investment goals in personal values

Our personal values are a central part of who we are. They are our deeply held beliefs about what is important in the way we live, the way we work, and the way we interact with others. They determine our priorities and the measures against we judge ourselves.

Living according to our values can make us happy, just as behaving in a way that is inconsistent with our values can be a source of discord in our lives.

In an investment context, we are likely to be more disciplined and focused on pursuing goals that are grounded in our values, where the emotional link is stronger.

From an advisor’s perspective, determining a client’s values is therefore critical.

Expert insight – goals connect advisor and client

“I think of goals as a great framing agent, that can really connect the advisor to the client.” David Bell

Expert insight –behaving in line with values is the key to happiness

“Values control all our decisions, conscious and unconscious. If we aren’t always moving towards out values, we experience dissonance.”Katherine Hunt

A model of personal values

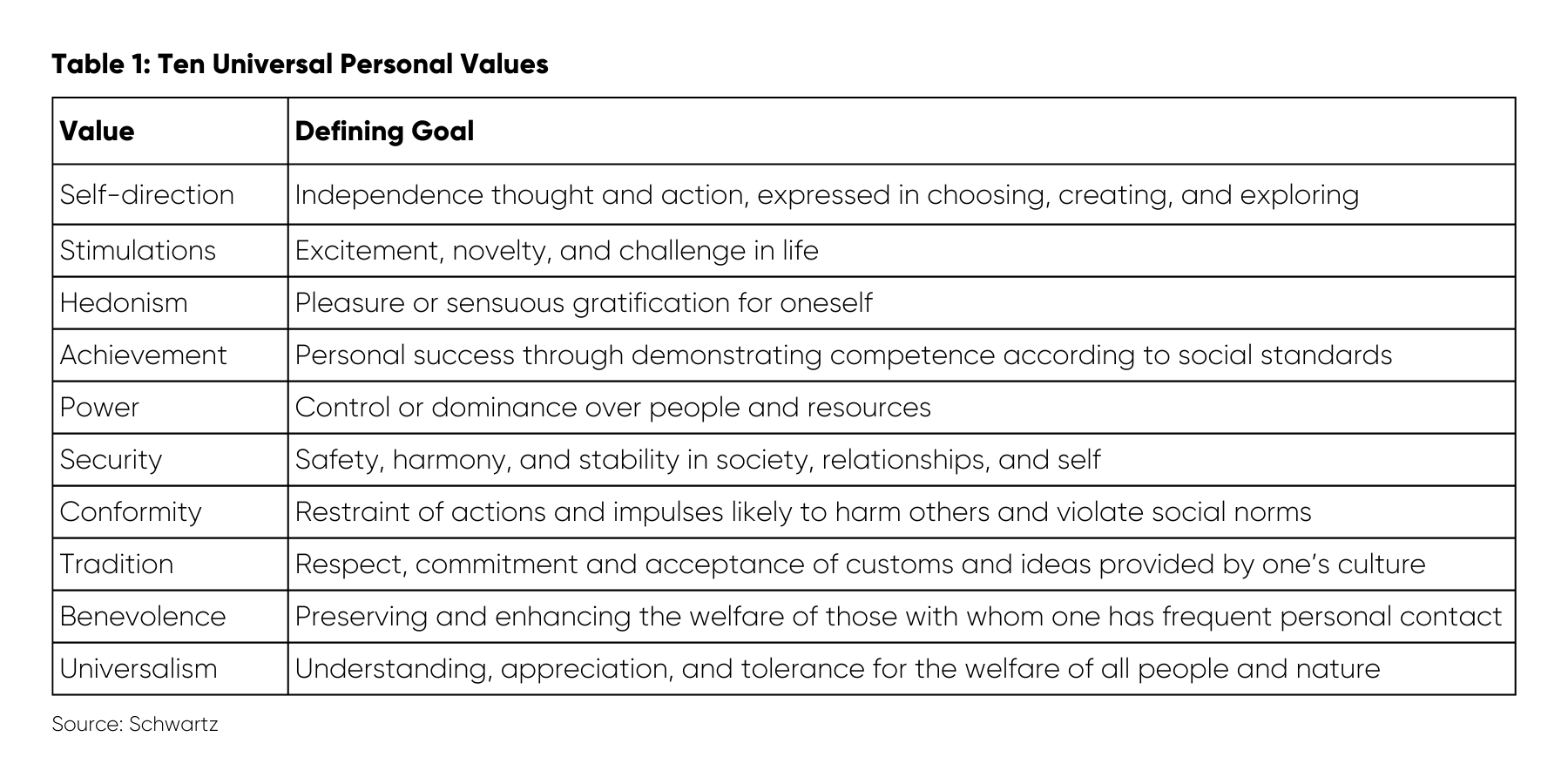

While there are many frameworks of personal values, one of the most frequently referenced is that created by Shalom Schwartz12.

In his framework, Schwartz identifies ten basic human values, each distinguished by their underlying motivation or goal, and each recognised across all cultures.

Turning values into investment goals

Whereas the term ‘values-based investing’ has been co-opted by some to mean ESG or impact investing, true values-based investing simply means investing in line with ones values.

Any of Schwartz 10 universal values can give rise to an investment goal, as illustrated by the selected examples below:

• Self-direction can be thought of as financial and emotional freedom, which saving for retirement can be seen as. Financial freedom will of course look different for each individual, which is why commonly used benchmarks such as the ASFA Retirement Living Calculator are of limited value.

• Hedonism can be behind the plans to travel or acquire a car, or live a particular lifestyle

• Stimulation can also be a driver of the desire to travel, or take on particular pastimes or courses of study (which can also be driven by the need to achieve)

• Tradition can be behind important intergenerational wealth goals; and

• Security is one of our most fundamental needs as humans, and is a key driver of the need to grow and protect wealth

Do advisers have the tools to truly determine client values?

Determining underlying client values in order to create linked investment goals can be challenging, for a number of reasons.

Clients may be reluctant to share such deeply held beliefs with their advisor, particularly in the early stages of an advice relationship. Other clients may be willing to open up, but simply struggle to articulate what their values are, perhaps because they have never consciously thought about them.

Expert insights – how to talk to clients about values

“I will prompt them with ideas, using examples I have seen with other clients. I will mention clients who want to leave inheritances for their children, or support a charity or learn a language and travel to that country. I will try and inspire them to generate their own ideas. I find the more examples you give them, the more they understand, and the easier it becomes.” Patricia Garcia.

“It sounds obvious, but active communication skills are key. In the early stages of working with a new client my focus is all on building rapport, so they feel safe end free enough to really open up and talk about themselves. They end up doing most of the work.” Antoinette Mullins.

“There’s a famous saying that we want to pass on our values, not our valuables! There’s no doubt that the idea of passing values down to younger generations can be very empowering. As advisors we can facilitate that intergenerational transfer of values and valuables.” Katherine Hunt.

Some advisors may also be uncomfortable straying away from financial matters and into conversations about emotions.

Advisors thus have a number of ways they can approach this process.

Firstly, they can utilise one of the many methodologies developed by psychologists to help clients express and prioritise their values.

Examples include:

• The life aspirations exercise, first found in the book Conscious Finance13, which involves clients writing down what they would do in a world without restrictions (financial, time, talent or other)

• The values card sort, where clients are presented with up to 100 cards (widely available online), each depicting a value, and asking them to rank them based on an immediate reaction

• George Kinder’s three ‘’life planning questions’ can help clients uncover priorities that may not be getting the attention they should be, and

• Life in perspective tools, such as the Life Calendar tool14, created by US writer Tim Urban, which shows one box for every week of a person’s 90-year life expectancy.

Closer to home, some widely available and popular client engagement software offerings incorporate questionnaires and other tools that can be used to capture, report on, then discuss client values.

But perhaps far more effective is to let clients gradually reveal their values, not through some formal, scripted question and answer process, but gradually over time, in response to more nuanced and open-ended questions about their hopes, their dreams, and their lived experiences.

Expert insights – advisors play the role of counsellor and psychologist

“People’s money values can be shaped by lived experiences, their families, traumatic events. Understanding the money psychology of an individual is critical to predicting their money behaviours.” Antoinette Mullins.

“Advisers have to be a little bit psychologist, a little bit counsellor, but we aren’t trained that way. That’s why soft skills are so important.” Patricia Garcia

A fresh – behavioural – perspective on risk

The way we define, and mitigate, risk is a foundational concept within investing and within financial advice.

Historically, a typical approach to risk would involve the client completing a questionnaire designed to elicit their tolerance for investment losses, the responses to which would see them classified into one of several investor profiles (e.g., conservative, balanced, aggressive).

But such an approach is problematic at several levels. A watershed study15 by Carrie Pan and Meir Statman of Santa Clara University concluded that typical risk questionnaires used to assess a client’s risk profile were deficient in 5 ways.

1. Every individual investor actually has a multitude of risk tolerances for each of their mental accounts (such as retirement planning or saving for a holiday) and trying to zero in one ‘umbrella’ tolerance will fail to identify these multitudes.

2. The links between answers to questions in risk questionnaires and recommended portfolio allocations are governed by opaque rules of thumb rather than by transparent theory.

3. Investor’s risk tolerance varies over time, and as investment markets rise and fall. Exuberance from the rises inflates risk tolerances, while sliding markets bring fear and deflated risk tolerances.

4. Risk tolerance varies when assessed in foresight or hindsight. Moreover, hindsight amplifies regret. Investors with a high propensity for hindsight and regret might claim, in hindsight, that their adviser overstated their risk tolerance.

5. Other propensities such as trust, and overconfidence, play an important role, yet are not addressed through traditional questionnaires. Trust makes clients easier to guide, while overconfident individuals tend to overstate their risk tolerance.

In the context of a goals-based approach to investing, two more shortcomings could be added to the above list; firstly, risk is viewed as the loss of capital, rather than the more relevant risk of not achieving the client’s goals, and secondly, this traditional framework makes no allowances at all for the emotional and cognitive biases that drive investor behaviours in the real world.

Expert insights – the dynamic nature of risk

“Retirement savings is an obvious area where risk tolerances change over time. I talk to my clients about the Retirement Risk Zone, which is the point at which sequencing risk becomes more pronounced, and the tolerance [for negative returns] can drop considerably.” Patricia Garcia

“The idea that you have one single risk tolerance for every aspect of your life, including all your goals, and everything that occurs through life, is just absurd.” Dan Miles.

A different approach to portfolio construction

A contemporary approach to portfolio construction must recognise and mitigate these shortcomings, in three important ways:

1. Risk tolerance must be assessed on a goal-by-goal basis

2. Goals must be prioritised

3. A more dynamic and adaptive approach to risk benchmarking – that recognises investor behavioural tendencies – is needed.

Assessing risk tolerance on a goal-by-goal basis

Individual client goals can vary widely in their timeframes, constraints, size, and importance. Rather than one static, umbrella risk tolerance, clients are likely to apply different risk tolerances to each individual goal.

In a way this can be seen as a form of mental accounting, where different goals are thought of as buckets, and the approach we take to each bucket is different.

Provided those goals can be clearly defined and separated, dialling the investment risk up or down by goal, and over time, can be fairly straightforward, and is something many advisers already do, with various degrees of formality (some may go as far as creating a different risk profile for each goal).

As an example, it would not be uncommon for an adviser to recommend a younger client take a more aggressive approach to their inaccessible superannuation savings than with their non-super investments.

Similarly, a retiree may invest their retirement savings in different buckets with different levels of risk, such as one for their base level of income, and one for travel and luxuries.

Expert insights – joining the dots between a client’s goals and their investments

“When you construct different portfolios aligned to different goals, it’s easier for clients to understand why they own the assets they do, and why they are taking the amount of risk they are. They can more easily join the dots between those things and their end goals, which can help them avoid surprises.” Dan Miles.

“Framing risk in terms of goal achievement can actually help people understand the need to take more risk in some circumstances. When you can show that investing all your retirement savings in cash will almost certainly not achieve your retirement goals, then you can start to have a more informed conversation about the nature of risk.” David Bell

Expert insight – the bucket strategy in action

“The bucket strategy concept is an easy one for client to understand. They might have 5 or 10 different goals, each with different timeframes, say short, medium, and long-term. You can then work backwards to determine the amount of money needed and the risk that needs to be taken. If there is a difference between the risk needed and the risk they can tolerate, then you need to go through a process of working that out with your client to help them prioritise and weight up the pros and cons of capacity to take risk and need to take risk.” Patricia Garcia

Expert insight – ESG preferences can also vary between goals

“You find people view their super and non-super investments differently. Younger people in particular can feel disconnected from their super, and some talk about their non-super investments as my money, as if there super somehow isn’t real. As well as different risk tolerances between super and non-super, we often find different attitudes towards responsible investing, with clients placing a higher priority on their own (non-super) money being invested ethically.” Antoinette Mullins

Prioritising goals

In order to determine the tolerance for risk at an individual goal level, advisers and clients need to understand the risks and consequences of not achieving a particular goal, and the importance placed on that goal by the client.

The more important the goal, the lower the tolerance for risk may be.

One way of assigning these priorities is to use a process akin to Maslow’s Hierarchy of needs.

Under Maslow’s theory, humans prioritise the need for safety, shelter, and food first, before moving onto other needs such as love, connection, self-esteem, and – at the top of the pyramid – self actualisation.

It is easy to see how this can translate into a framework for prioritising investment goals. A retiree for example will likely prioritise the need for an income stream to pay for the essentials, while goals associated with travel, funding their grandchildren’s education, or leaving a bequest to their favourite charity might be lower order priorities for which they are happier to take more risks in order to achieve.

(Not so) modern portfolio theory

Under Modern Portfolio Theory, which assumes rational investor behaviour, investors put all their assets in one portfolio. It is a theory which makes no allowance for investors having different goals and dynamic risk tolerances, and as such has little practical relevance to individual investors.

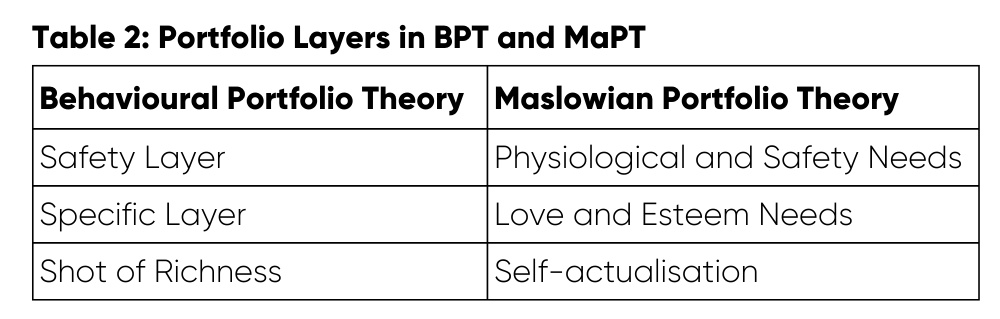

The utility of Maslow’s hierarchy in an investment setting has been widely recognised, and indeed has given rise to its own Maslowian Portfolio Theory (MaPT), itself a type of Behavioural Portfolio Theory (BPT).

Under Behavioural Portfolio Theory, portfolios are built in layers, with the base layer devised in a way that it is meant to prevent financial disaster, whereas the uppermost layer is devised to attempt to maximize returns, a ‘shot at richness’.

Risk benchmarks need to focus on the journey as much as the destination

A major downside of the traditional, static, view of risk is that the focus often becomes the destination, not the journey.

A client’s circumstances (objectives, timeframe, stated risk tolerance) may theoretically translate to an aggressive or growth profile in their investments, but when faced with the reality of portfolio losses they are mentally unprepared for, all those biases (including loss aversion) can rear their heads, and value destructive behaviours can start to creep in, turning observed losses into realised losses.

A bit like a rollercoaster where the finish is higher than the start, people might be happy with the end point, and say they are happy to take the ride, but when faced with the reality of the stomach-churning dips, they want to get off.

Expert insights – averages can be meaningless, it’s the extremes that matter

“Taking a linear approach and talking about averages when defining risk, is a bit pointless, because the average won’t happen, the average will just sit near the middle of a whole bunch of movements up and down, and it’s those movements the client cares about.” Dan Miles

Australian investors exhibit high loss aversion

The 2023 ASX Investor Study16 found that more than two thirds of investors had a preference for guaranteed and stable returns over more variable, higher growth options. Somewhat surprisingly, this preference was high even for younger investors.

Retirees also exhibit a strong preference for stability and predictability, a point reinforced by 2018 research17 released by National Seniors Australia.

Their study of 5,000 members found:

• 23% could not accept any annual loss on their portfolio

• Around 40% could only accept 5% or less

• Only 7% could tolerate a loss of 20% or more

Applying a real-world perspective on this, between 1920 and mid-2022, there were 46 market falls of 10% or more18. Almost one third of these (15) have occurred since January 2000.

Expert insights – client fears are revealed under pressure

‘Clients might say they would be fine with a 20% or 30% drop in their portfolio, but when the rubber hits the road, they say ‘oh no, I wasn’t ready for this at all.” Katherine Hunt.

“One book that influenced me greatly was ‘Mean markets and lizard brains19’, which talks about our primitive tendencies to avoid conflict and bail when something gets too hard. Fear can be a powerful motivator of behaviour, and when clients see large losses, the fear can be real. You’ve really got to invest a lot of time up front in managing and minimising that fear.” Antoinette Mullins

Investment ‘Sticker shock’ can lead to bad behaviour

When investors experience a portfolio loss outside of their expectations, the ‘sticker shock’ can evoke a visceral reaction and set off a chain of behaviours that destroy value in their portfolios.

Although clients are told to hold the line, and that losses aren’t losses until they are actually realised, seeing a negative number on a screen can still create a great deal of panic.

Sticker shock was prevalent in 2022, a year that defied normal expectations, not because equity markets experienced losses, but because – for the first time in decades – equity markets and fixed interest markets were positively correlated, meaning they moved in the same direction (down). Orthodox thinking about the defensive nature of fixed income was thrown into question, as many investors nursed significant losses.

Expert insights – advisors lack the tools to solve new era problems

“I’m not sure we have the tools to address today’s problems, because we haven’t had today’s problems before. Plummeting bond yields, rising interest rates, overvalued and hyper volatile markets. It feels like there are no safe assets at the moment, defensive isn’t truly defensive.” Patricia Garcia.

“I think as an industry we can do a better job of providing advisors the tools to do stochastic modelling. To be able to show a client that based on thousands of possible scenarios, there’s a 90% chance your money will run out before age 70, for example, is incredibly powerful. Similarly, you can show how, even though the future is uncertain, you’ve at least tipped the odds in their favour with the way you’ve built a portfolio.” Dan Miles

Avoiding sticker shock

There are a number of ways advisors can help their clients avoid investment sticker shock. Setting client expectations is important, as is a commitment to continually improving the financial literacy of your clients.

But another way is to invest in a way that is more closely aligned to their risk tolerance for each goal, and which limits the instances of stepping outside those risk comfort zones.

This doesn’t necessarily mean adopting an overly cautious approach – as that can itself increase the risk of not achieving clients goals because it limits growth potential.

Rather, it can mean using a wider range of metrics by which to benchmark risk, and building client portfolios accordingly.

Expert Insight – focus on progress towards goals rather than absolute performance

“When your focus is on goals rather than absolute performance, the obsession with market movements can be minimised somewhat.” Antoinette Mullins

Beyond volatility – using a broader range of risk metrics when constructing portfolios

Volatility has traditionally been the most common measure of risk used by advisors. But for all its merits, it also has its limitations, including:

• Although volatility can be positive or negative, it treats all outcomes the same

• It doesn’t reflect all the risks that can face an investor, such as the risk of not generating enough capital growth

• Due to misconceptions in the way volatility is calculated, many people falsely believe that two investments with the same standard deviation are equally risky

As well as utilising a more comprehensive view of volatility – which reflects its limitations, a broader range of risk metrics could include:

• The maximum drawdown a portfolio could bear

• The average magnitude of drawdown, and

• The frequency with which a significant drawdown might be expected

Using such a range of risk benchmarks would allow scope to:

• Build portfolios more closely aligned to the way investors cope with risk in the real world

• Build portfolios that maximise growth potential without breaching risk comfort zones.

Expert insight – breaching risk guard rails can drive value destructive behaviour

“I think that all goals-based investments should be benchmarked to the amount of risk they have said that they can tolerate for each specific goal. Because if you breach that, you’re going to get these behavioural responses that can be very destructive. A lot of people that say things like, capital losses don’t count unless they’re realised. Well, let’s be honest, human beings, when they see negative things on the screen, it leads to a visceral response and a behaviour that sees them realise that loss, all because they weren’t expecting that result.” Dan Miles

Expert insight – more consistency needed in provider risk labels

“I think product providers and fund managers can do a better job of categorising and describing risk. There’s no consistency. Take balanced for example, most people would expect balanced to mean 50% growth and 50% defensive allocations. But I’ve seen balanced funds that are as much as 60% or 70% growth, which can be confusing.” Patricia Garcia

The importance of financial literacy

Financial literacy is a key pillar of financial consumer protection.

In July 2020, the final report of the Retirement Income Review20 was handed to the federal government. That report found lower levels of financial literacy were associated with:

• Lower super balances

• Lower willingness to take financial risk

• Shorter savings horizons

• Being less likely to set up a retirement plan

• Being less informed about pension rules

• Paying higher investment fees

• Not diversifying pension assets

From a financial advisor perspective, financial literacy also underpins genuine informed consent. Clients who understand the nature of investment markets will be better prepared for the inevitable ups and downs, and for this reason many advisors prioritise client education as a core part of their advice and client engagement processes.

While Australian financial literacy is high relative to many of its international peers, various studies have identified alarmingly low levels of literacy among older Australians, including retirees.

Expert insight – ambiguity aversion and the need to lift financial literacy

“We talk a lot about the dimensions of risk, and I think one that gets overlooked is ambiguity aversion. Someone might be highly tolerant of risk they understand, but not risks they don’t. In a finance sense it might mean clients aren’t actually risk averse, it’s more that they don’t understand financial concepts and financial risks, and so taking steps to lift their literacy can become critical to accurately matching clients to risk”. David Bell

Expert insights – the importance of communication

“I’ve always said to my team, 50% of our job is to run the client’s money, and the other 50% is to communicate with them, telling them what we are doing, why, and how. If they don’t understand that, they are more liable to get surprised. And no one likes surprises, especially when money is involved.” Dan Miles.

“We focus so much on education and communication upfront, so the phone doesn’t ring off the hook every time the market gets a little choppy.” Antoinette Mullins

Summary

As humans, our limited capacity to process information and make decisions is constantly being challenged by the increasing amount of data we are exposed to in our daily lives. The only way we can make decisions is to employ shortcuts, basing decisions on emotional and cognitive behavioural biases.

Decisions grounded in these biases can be problematic, especially when they’re related to important issues such as our finances, and there is a large body of evidence showing how behavioural biases translate into poor investment performance.

By grounding investment goals in a client’s personal values, better aligning is://innovaam.com.au/ndividual goals with variable and evolving risk tolerances, and constructing differentiated portfolios to reflect these goals and risk tolerances, advisors can create more client ownership and understanding of the investment strategy used for each goal, thereby avoiding surprises, and minimising the likelihood of value destructive behaviour.

References

01 https://hbr.org/2019/08/6-reasons-we-make-bad-decisions-and-what-to-do-about-them

02 https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1018033108

03 https://www.britannica.com/science/information-theory/Physiology

04 https://www.fastcompany.com/3051417/why-its-so-hard-to-pay-attention-explained-by-science

05 https://www.ifa.com/articles/dalbar_2016_qaib_investors_still_their_worst_enemy

07 https://www.professionalplanner.com.au/2023/09/adviser-value-worth-5-9-pc-in-2023-report/

08 https://www.amazon.com/Behavior-Gap-Simple-Doing-Things/dp/1591844649

09 https://www.morningstar.in/posts/68952/the-gap-between-investor-return-and-investment-return.aspx

10 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loss_aversion

11 https://finance.yahoo.com/news/warren-buffett-says-simple-rule-180552807.html

12 https://i2insights.org/2022/05/10/schwartz-theory-of-basic-values/

13 https://www.amazon.com.au/Conscious-Finance-Uncover-Beliefs-Transform-ebook/dp/B0027P9PUC

14 https://waitbutwhy.com/2014/05/life-weeks.html

16 https://www.asx.com.au/content/dam/asx/blog/asx-australian-investor-study-2023.pdf

17 https://nationalseniors.com.au/uploads/07183036PAR_OnceBittenTwiceShy_Web_0.pdf

18 https://www.firstlinks.com.au/market-fall-reveals-risk-tolerance-loss-aversion

19 https://www.amazon.com.au/Mean-Markets-Lizard-Brains-Irrationality/dp/0471602450

20 https://treasury.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-02/p2020-100554-udcomplete-report.pdf